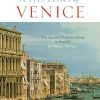

A History of Venice

£5.70

‘Norwich has loved and understood Venice as well as any other Englishman has ever done’ Sunday Times

‘Will become the standard English work of Venetian history’ Financial Times

___________________

Renowned historian, and author of A Short History of Byzantium, John Julius Norwich’s classic history of Venice

A History of Venice tells the story of this most remarkable of cities from its founding in the fifth century, through its unrivalled status for over a thousand years as one of the world’s busiest and most powerful city states, until its fall at the hands of Napoleon in 1797. Rich in fascinating historical detail, populated by extraordinary characters and packed with a wealth of incident and intrigue, this is a brilliant testament to a great city – and a great and gripping read.

___________________

‘The standard Venetian history in English’ The Times

‘Norwich has the gift of historical perspective, as well as clarity and wit. Few can tell a good story better than he’ Spectator

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | 2Rev Ed edition (3 July 2003), Penguin |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| File size | 71614 KB |

| Text-to-Speech | Enabled |

| Enhanced typesetting | Enabled |

| X-Ray | Not Enabled |

| Word Wise | Enabled |

| Sticky notes | On Kindle Scribe |

| Print length | 676 pages |

by Nicholas Casley

This review refers to the 2003 Penguin edition, which consists of what had been two separate books issued in 1977 and 1981 respectively, namely “Venice: The Rise to Empire” and “Venice: The Greatness and Fall”. Both books had been combined into one volume by Penguin in 1983. (For those wanting details of the city’s history after 1797, John Julius Norwich has produced a quasi-successor volume, “Paradise of Cities: Venice and Its Nineteenth Century Visitors”, but, as its title indicates, this is as much concerned with prominent outsiders than with the city itself.)

Since the one-volume history was published in 1983, there has been no revision of the text; neither has there been an update of the bibliography nor the writing of a new introduction. That said, the introduction that remains is a marvellous piece of personal writing in itself, presenting to us in an engaging manner the author’s initiation into Venetian world, of which he is now probably the most senior and most knowledgeable English member. He writes in his introduction that this book is an attempt to fill the gap in the market for an up-to-date general consecutive history of Venice that tells “the whole story … from her misty beginnings to that sad day” in 1797 when the final Doge passed removed his cap for the last time. But how can “the whole story” ever be told? In fact, and surprisingly so, this book’s story is extremely partial.

The scope of this work is immense, not only in terms of time – from the origins of Venice in the dark days of the late Roman Empire up to the ending of the republic by Napoleon in 1797 – but also in terms of place. For what this volume is not, is a history of Venice as a city; rather it is the history of the Venetian Republic as a diplomatic entity and its relations with other powers. We spend less than half our time in Venice itself; more likely, we are in Milan with the Sforza dukes, or in Rome with the Pope. The French, the Spanish, the Germans also make regular appearances on the Lombardy plain of northern Italy. However, even this area is often a sideshow to the main theatre that is the eastern Mediterranean: Corfu, Crete, the Peloponnese, Cyprus, and, of course, Constantinople are at the heart of this story. The writing is full of what the author describes as those “sudden shifts of focus which make the history of the Mediterranean so bewildering to writer and reader alike”. The book contains a number of maps gathered together at the beginning. Make a good perusal of the first, for it is the one that you will need to refer to time and time again. It shows the greatest geographical coverage, from Genoa in the west to Jerusalem in the east, and from Vienna in the north, to Cairo in the south.

So, to some extent, this book is not the book I expected or wanted to read. I often felt as if I was reading a displaced version of A.J.P. Taylor’s “The Struggle for Mastery of Europe, 1848-1914”. Less time is spent in the lagoon than in Lombardy and the Levant. I wanted to read about the development of a very special city. Whilst there is much here about the politics of the place, its Doges, its councils, its political (and, to a lesser extent, economic) development, there is precious little about how the landscape of the city developed, how the buildings were constructed, how the canals were dug, how the people lived and worked and spent their spare time. For these, you must go elsewhere. (Indeed, beware the opening chapters that tell the story of the origins of Venice. Since they were written, new archaeological discoveries have radically reshaped the story, so that we are now aware of a heavier Roman presence than was first thought, and we can see more clearly that the city’s streets and canals often derive from a grid-plan of agricultural estate boundaries.)

John Julius Norwich was born in 1929, and so perhaps his concentration on political and diplomatic affairs, on the wars fought on the plains of Lombardy and the naval battles won and lost in the Mediterranean, is a product of his generation’s historical perspective. I say this because it is strange to see him refer to “painting and sculpture, music and architecture, costumes, customs and social life” as digressions from the history he wishes to tell. He concedes that he often found it difficult not to digress, and provides cogent reasons why he does not do it more often. All the same, it is a curious history of Venice that gives Casanova one entry in the index, but Charlemagne nine. Sure Casanova played little if any part in the city’s history, but he is a metaphor for its eighteenth-century culture and his falling foul of the city authorities is a good example of how the state then treated crime and criminals.

At the commencement of chapter 45 on the long eighteenth century, the author allows that not much happened in the political arena, as the city’s economy continued its decline and the most serene republic gave itself over more towards sensual pleasure than puritan commerce, and so a more episodic and less chronological approach is adopted. At the start of the book he mentions that all political historians concur in giving the eighteenth century short-shrift in their works on Venetian history. John Julius Norwich thinks that readers might feel that he is running out of steam, but this reader does think that he has been short-changed in this regard, for whilst indeed the politics of this century may have been parochial, what an opportunity arises therein to explore how and why this should be so.

Whilst the scope of the story is immense, the author is certainly aware that his version cannot even hope to do complete justice to the tale even when he is dealing with purely military or political issues. In his introduction, he admits to forsaking profound detail in the interest of keeping the story moving. He writes, “The one luxury I have allowed myself has been the occasional reference to buildings and monuments still standing today which have a direct bearing on the events described.”

I learned a great deal. I learned how often the republic was saved by the sudden death of its opponents, this event occurring often enough for me to have my suspicions that the famed strength of Venetian diplomacy incorporated some clandestine, but clearly undiplomatic, skills. I learned also about the relatively benign approach to religious tolerance adopted by the Venetian government, refusing to cower to the more extreme Counter-Reformation policies of the Papacy and insisting that the crimes of the clergy be treated on an equal footing as the crimes of any other citizen. I learned how the detailed treatment in the book about the development of municipal (and imperial) government helped explain the character of her actions and of her people – and vice-versa. Indeed, I came away from this book with quite a profound admiration for the Venetian political system, with its in-built determination to prevent dictatorship or even the cult of personality. I feel we can learn much today from this refusal to endorse political celebrity, as well as from the republic’s seemingly bizarre electoral system that relied on a mixture of elections and chance to appoint the Doge and other chief officers. Whilst clearly an oligarchy, it nevertheless provided internal peace and stability to enable the city and republic to face external threats. (The author also clearly betrays his sympathies for the success of the political system, but I did often wonder whether I was only hearing one half of the story.)

But I learned very little about the rise and decline of human occupation on other islands in the lagoon. For example, the island of Torcello at its greatest extent once had twelve parishes and sixteen monasteries, as well as its cathedral. Aerial shots of the area now show mostly gardens and grass, but in the surrounding mudflats can be seen channels that were clearly once man-made canals. What happened? We are not told. I also learned next-to-nothing about how the Venetians countered the effects of flooding and erosion. There is a short reference to the city employing mercenaries in the twelfth century to fight the Paduans over the latter’s attempts to divert the course of the Brenta as it entered the lagoon, but there is no attempt to explain the geography behind this issue in any detail. Another area that demands more attention is the handling of the relative economic decline of the city and empire as trade routes eastwards around the Cape of Good Hope waxed at the same time as its political control of the eastern Mediterranean waned. In what ways did the merchants of Venice make their money in these new conditions?

There are five maps. This edition also comes with 59 black-and-white plates, some of use, but anyone who has visited Venice will feel hard done by not to have the vibrant colour of the city not mirrored in a book about its history. The bibliography is extremely useful for further exploration, but alas, there is nothing later than Jan Morris’s “Venetian Empire” of 1980. The index appears fine at first glance, but displays deficiencies when used. For example, the index shows only one entry – page 99 – for St Mark’s Campanile but misses that on page 280; the reference to legislation against the Jews is indexed at page 602, but there is nothing indexed for the information on page 273; and there are no entry for “Carnival”! (As for that entry on page 273 about the treatment of the Jews, the author’s very words belie the meaning that he probably intends, and is one of the blessedly few times in which he perhaps displays a lack of objectivity in his love for the city.)

Some will think me unfair in my criticisms. For, if truth were told, the volume as a whole is a magnificent achievement, and has rightfully been praised as an accessible introduction to Venice’s history for the general reader. The author’s style is engaging and down-to-earth. He carries the reader along with him, to Milan and Ferrara, down the Adriatic to Albania and Ancona, across the seas to Tyre and Constantinople. His is an assured and often breathless journey and it is a pleasure to accompany him. It is just a shame that so little time is spent on San Giorgio Maggiore, or in the Arsenale, or in the markets of the Rialto. But even within the confines of the city, there are still some incisive and wonderful glimpses of the city to be had, for example the author’s brilliant critique of the Rialto Bridge at the end of chapter 38: “Only very occasionally do we suddenly, unexpectedly and momentarily see it for the mediocrity it is.” With this mixture of fine writing combined with a flair for vivid story-telling and an eye for historical argument, the reader of this book will reach the end intellectually enriched and have his or her curiosity for further exploration kindled.

by Neil S.

I would give the book three and a half stars. Can be a little opinionated at times without justifying those views with objective reasoning. However, an informative account of the history of the Republic and the author has a very easy style of writing which makes this book very easy to read.

by Gal

I’m still working my way through it, but like JJN’s earlier histories (for example, on Byzantium) it provides a wealth of detail and is written in a clear and engaging style. Strongly recommended for anyone who’s interested in the surprising history of this, one of Europe’s earliest republics.

by Philip Meers

This is a real page turner. I kept turning pages through sheer and utter boredom.

I cannot fault the research. It is certainly a detailed examination of the political history of Venice. However, this history is on auto-replay, and the events, and worse still the names seem to repeat, again and again, to the extent that it seems as if the centuries may change, but the story is just a version of the previous chapter.

The style of writing is, ironically for the wettest of cities, as dry as dust. Little attempt has been made to make this an enjoyable read. It is like the worst of A Level texts, long, tedious, and full of worthy facts that will appear on the exam paper.

What I dislike most is the authors use of foreign quotes. Some are provided with translations, but not all. Does he do this to show his infinite superiority? Is it a compliment to the reader that we are on his level? I suspect the former.

Although I am an historian, my knowledge of Italian history is limited. Lately, I have been expanding my knowledge, and, thankfully, this is not the first book I have read about Italy, or even Venice; had it been my first, it very well could have been my last.

I am glad that I only spent 99p on this, though for the amount of enjoyment I’ve had reading it, I feel I should have a 98p refund!

I cannot recommend this to the average reader. Even as an examination text, it would be a difficult read.

by Helen Musson

Brilliant!

by bxbspringboard

This is a sweeping history of the Republic of Venice, a city central in the affairs of Europe for nearly a thousand years. Written with a light touch and with an eye for the amusing anecdote it allows both an understanding of Venice’s place in the overview of European history and an insight into the city, its institutions and its personalities. I enjoyed it enormously…

…bar one thing – the quality of the Kindle Edition. It is studded with errors that presumably arise from the Kindle edition being an OCR of a print edition. These are not minor irritations. They obscure crucial dates as well as providing jarring interruptions to the flow of the writing. As examples:

more likely to have affected them when, on i z August 976 Read more at location 1053

Finally on n May, Read more at location 1206

HauteviUes Read more at location 1907

well over ioo ships, Read more at location 2646

very litde else. Read more at location 2958

fleet of ioo ships Read more at location 3454

to the effect that in @IJOOhe Read more at location 3678

with genera) enthusiasm; Read more at location 4527

mqdest measure, the Duke’s confidence. Read more at location 5606

(I have not reflected this in the star rating since it seems to me an issue with the Publisher rather than the book and author. I would, however, query whether to buy the Kindle edition on this basis.)