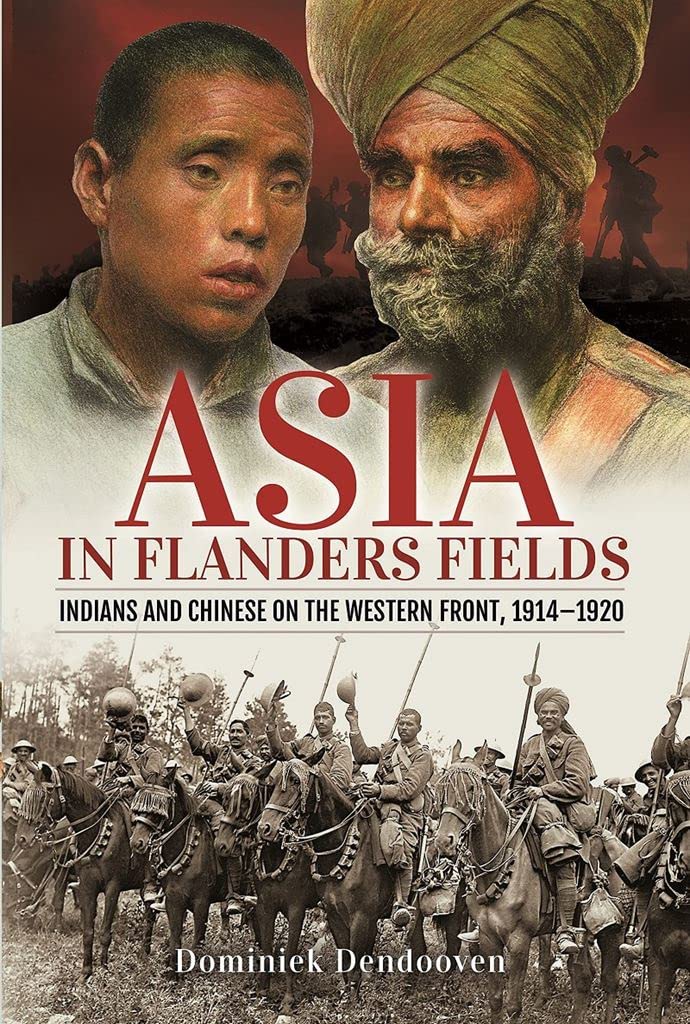

Asia in Flanders Fields: Indians and Chinese on the Western Front, 1914 1920

£23.70

The First World War brought peoples from five continents to support the British and French Allies on the Western Front. Many were from colonial territories in the British and French empires, and the largest contingents were Indians and Chinese – some 140,000. It is a story of the encounter with the European ‘other’, including the civilian European local populations, often marred by racism, discrimination and zenophobia both inside and outside the military command, but also lightened by moving and enduring ‘human’ social relationships. The vital contribution to the Alles and the huge sacrifices involved were scarcely recognised at the Paris Peace Conference in 1918 or the post-war victory celebrations and this led to resentment – see huge media coverage in 2021. The effect of the European ‘other’ experience enhanced Asian political awareness and self-confidence, and stimulated anti-imperialism and proto-nationalism. This is a vivid and original contribution to imperial decline from the First World War. and the originality of the work is enhanced by rare sources culled from original documents and ‘local’ European fieldwork – in French, German and Flemish.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | Pen & Sword Military (10 Dec. 2021) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Hardcover | 256 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 1526763338 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1526763334 |

| Dimensions | 15.88 x 2.54 x 23.5 cm |

by ROBERT NEIL SMITH

In Asia in Flanders Fields, museum curator and historian, Dominick Dendooven analyses the Indian and Chinese contingents on the Western Front. These groups are understudied and undervalued in popular culture and remembrance of the Great War, yet they stood in the same mud and bled the same colour as their European counterparts. Their sacrifice is certainly worthy of more than a mention in the history books. Dendooven’s book may finally have changed that tide.

Dendooven begins with Indians on the Western Front: who they were and what they did. The Indian Army Corps took part in the fighting, though the infantry divisions left in 1915. The British originally did not want them there in the first place, arguing on purely racist grounds. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this is a recurrent theme throughout Dendooven’s account. India also supplied a significant number of labourers. Both Indian contingents initially experienced the war as a completely alien environment with few friendly faces; the YMCA was a peculiar but perhaps exaggerated exception. The civilian population and Indians got on reasonably well given the circumstances, and sometimes too well, Dendooven notes. He devotes a chapter to Indian Prisoners of War who were fortunate when grouped together but otherwise endured in bleak isolation, though the Germans were usually decent captors. Whatever their fate, Indians learned from their WWI experience, and some returned to affect change in India.

It might come as a surprise, but 140,000 Chinese served on the Western Front, 96,000 with the British as the Chinese Labour Corps. Dendooven remarks that they are almost entirely forgotten to history. Britain did not want the Chinese in Flanders, but they needed the manpower after the Somme. China wanted a seat at the post-war table and contracted out fit Chinese men. The British knew them by the number on their brass armband and maintained strict segregation, at least on paper; language was, of course, a significant barrier. The Chinese did not fight but suffered casualties from shelling, a clear breach of their contracts, which sometimes led to strikes and violence. Dendooven contrasts British attitudes to that of the Belgians who got on better with the Chinese, though that often broke down in the post-war period. Both exhibited xenophobia and racism towards the Chinese, and sometimes that was reciprocated. Dendooven concludes with an examination of the legacy of the Chinese labourers when they returned to China. Their impact was more indirect than that of the Indians but still significant.

I should note here that this is a work of social history; World War I provides the backdrop to most of the description and analysis in Dendooven’s book. He makes excellent use of mainly western primary sources, but Dendooven also makes the most of those from India and especially China, including interpreting their message laden artefacts. The picture he draws of the Indians and Chinese is probably as good as we are going to get with the sources available, but we should thank Dendooven and other like-minded historians who have picked up the cudgel for a transnational history of World War I on the Western Front.

by Old Soldier Sahib

There are probably two books here. The Indian contribution during the First World War has been largely neglected over the years and doesn’t get much of a look in here either, with just seventy pages devoted to the Indian effort. The Chinese fair slightly better and get the remaining hundred pages.

That’s not to say that what’s published here isn’t worth reading, it is, and the author clearly has a lot of empathy with his subjects. I just think that this would probably have been better as two books – one expanded and devoted to the Indian effort and the second with the focus on the Chinese Labour Corps which is another neglected and lesser studied aspect of the conflict.