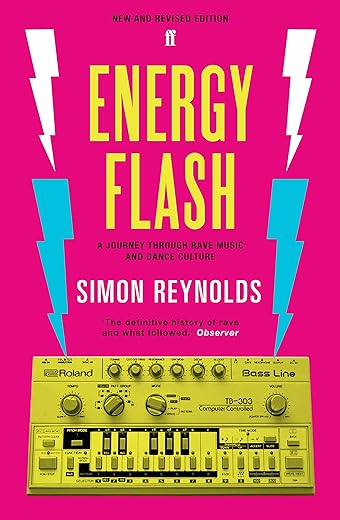

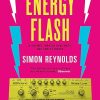

Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture

£14.60£19.00 (-23%)

Twenty-five years since acid house and Ecstasy revolutionized pop culture, Simon Reynolds’s landmark rave history Energy Flash has been expanded and updated to cover twenty-first-century developments like dubstep and EDM’s recent takeover of America.

Author of the acclaimed postpunk history Rip It Up and Start Again, Reynolds became a rave convert in the early nineties. He experienced first-hand the scene’s drug-fuelled rollercoaster of euphoria and darkness. He danced at Castlemorton, the illegal 1992 mega-rave that sent spasms of anxiety through the Establishment and resulted in the Criminal Justice and Public Order Bill. Mixing personal reminiscence with interviews and ultra-vivid description of the underground’s ever-changing sounds as they mutated under the influence of MDMA and other drugs, Energy Flash is the definitive chronicle of electronic dance culture.

From rave’s origins in Chicago house and Detroit techno, through Ibiza, Madchester and the anarchic free-party scene, to the pirate-radio underworld of jungle and UK garage, and then onto 2000s-shaping genres such as grime and electro, Reynolds documents with authority, insight and infectious enthusiasm the tracks, DJs, producers and promoters that soundtracked a generation. A substantial final section, added for this new Faber edition, brings the book right up to date, covering dubstep’s explosive rise to mass popularity and America’s recent but ardent embrace of rave. Packed with interviews with participants and charismatic innovators like Derrick May, Goldie and Aphex Twin, Energy Flash is an infinitely entertaining and essential history of dance music.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | Faber & Faber, Main edition (6 Jun. 2013) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Paperback | 816 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 0571289134 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0571289134 |

| Dimensions | 15.3 x 4.2 x 23.3 cm |

by Kevin Taylor

The book starts off well, very informative and for the most part correct. When the author gets to 1999 onwards he misses out the phenomenon that was hard house totally. In fact there is only one mention of hard house in the whole book and that’s one sentence. Bang, bang, bang music for dead brained people I think it says. Hard to remember as I’m numbed from the rest of the book. No mention of hard trance, indeed trance is glossed over. However if you want to know about clubs that got 100 people in on a good night in NYC in 2000 or weird genres that you’ve never heard of before (& for good reason) then this is the book for you. Definitely not up to scratch with equipment used by DJ’s both today and back in the day. I doubt he’s ever heard of a Numark 1775A or knows what one is. My advice, read the first third of the book then sling it in the bin.

by JoeSmooth

I’m on page 235 and the obvious bias towards the author’s favourite things is grating. And I was tempted to count the number of times he references Tangerine Dream. I’ve got 500 pages to go or more. I am not sure I can put up with a defence of the worst aspects of dance music which I have been checking on youtube as i go along so its not a blind comment im making. I will be back with another review later

by disturbedchinchilla

It’s a little ironic that Simon Reynolds, of all people, should choose to argue that dance music is at it’s best in its most lumpen, populist, apparently anti-intellectual form. Reynolds made his name in music journalism in the late eighties precisely because of his intellectual chops; he coined the term ‘post-rock’ after all, and his first full-length book (‘The Sex Revolts’, co-written with his partner, Joy Press) is largely an analysis of rock music through the perspective of post-structuralist gender theory. ‘Rip it Up and Start Again’, his most successful book to date, focusses on post-punk’s infiltration of the mainstream- a celebration of a time where experimental, politically aware bands enjoyed prime-time coverage on Top of the Pops. Similarly, during his tenure at Melody Maker, when Everett True’s gonzo-grunge-clown-prince schtick was in it’s ascendancy, Reynolds’ insightful, measured prose was often a refreshing counterbalance to the snarky polemic of his colleagues. He was chiefly known for his support of the more innovative ‘indie’ guitar acts: bands such as My Bloody Valentine, Young Gods etc. His embracing of Rave culture was all the more shocking at the time because the paper’s editorial line was militantly pro-‘alternative’ guitar music and anti virtually everything else.

So credit, where credit is due. Reynolds was one of the first ‘Rock’ journalists to do the dance thing. Originally published in 1998, ‘Energy Flash’ has undergone two updates in the last decade – perhaps evidence of its enduring significance as both a primer on and critique of Rave, it’s grandparents, cousins, nieces and nephews. On the other hand, it could be argued that the updates, together with a lack of revision of earlier sections, has resulted in particularly hefty Frankenstein’s monster. It’s certainly an exhaustive, if occasionally exhausting piece of journalism.

The opening chapters are still pretty essential – you get a solid pre-history covering Chicago House, Detroit Techno, Acid House and the first two waves of Rave in the UK. As the book progresses, it feels increasingly flabby and self-contradictory. Reynolds’ argument is totally convincing: listening to tracks like Joey Beltram’s own ‘Energy Flash’ now, you can’t help but be struck by how something so brutally simple (four to the floor, Roland 303 bass squidges) can be so powerful; there’s little of what could be called ‘melody’, there’s no narrative, but it engages totally as an experience in sound. Hardcore is at once leftfield in the extreme and defiantly populist. Never has ‘dumb’ been so clever.

Reynolds is spot-on in his critiques of ‘intelligent’ jungle and techno – effectively the digital equivalent of progressive rock – artists in these subgenres seemed to miss the point: dance music’s radicalism results from its functional aspects – it is ‘dance’ music first and foremost.

However, as the book progresses its painfully apparent that Reynolds can’t help but be drawn towards the ‘intelligent’ forms of dance music he claims to despise. In a chapter focusing on the German Mille Plateaux roster he performs somersaults of Deleuzian theory, only to return disparagingly to his ‘ardcore-knows-best stance in a withering little paragraph.

Parts of the book haven’t aged that well: Tricky is treated as a sort of Trip-Hop messiah. Sadly, he wasn’t, although his recent efforts betoken a partial return to form. An interview with Spiral Tribe is an interesting cultural artefact, but Reynolds’ wide-eyed acceptance of their leader’s risible psycho-babble is a little cringe-worthy.

Similarly, I’d advise skipping the prologue on MDMA. Ok, Ecstasy is an inextricable part of Rave music; the language and sound of late 80s and early 90s hardcore is saturated with the mythology of E; it is ‘drug’ music. But I’ve yet to come across a drug bore who isn’t, well, boring. Reynolds returns to MDMA again and again and again throughout the book, admittedly, sometimes with some perceptive comments (a chapter on the quasi-Religious nature of Ecstasy culture is particularly good), but often I felt like the poor unfortunate who gets trapped in the corner at a party, pinned-down by some endlessly enthusiastic space-cadet, chewing their face off (and your ears) on gak.

Reynolds also has some stylistic tics that are a bit of an acquired taste. Perhaps as a result of his interest in Deleuze & Guattari, Reynolds has always had a penchant for neologisms, he also has a habit of warping the morphology of terms for his own (often obscure ends). Check out ‘senti-MENTAL’ & ‘Hype(rbole)’ God knows what he means…

It’s still a damn good read (hence the 4 stars) even if it’s perhaps become more of a dip-in, dip-out text than a linear narrative (Reynolds’ would probably see this as ‘rhizomatic’). Much as he could happily hold his own in a forum with Slavoj Zizek and Paul Ricoeur, Reynolds is actually at his best at the battle-front of reportage. For instance, his description of a Gabba event in Arnhem is absolutely captivating; witness the love-crowd hunkering down to some crazed martial brutalism.

by Amazon Kunde

Everything as expected thank you. Recommend seller. Fine trade.

by Steven

I learnt a few things about early Detroit and the rave scene which was interesting but then the book tails off into loads of opinions about the club scene and obvious bias. Tricky gets almost a whole chapter but post 95 is passed over as superclub DJs being in it for the money with no music referenced at all. I grew up with Oakenfold as resident at Cream when it cost £5 to get in, less than the authors beloved raves. Barely a tune is mentioned and DJs like Sasha mentioned as if they just span a few tunes and did nothing else. Moves onto a bit of namedropping of artists like Burial but with constant throwback to rave. Couldn’t tell you how the book ends because I couldn’t bring myself to finish it yet.

by Stevie E

Thanks

by Erlö Sung

Quite remarkable really, and it’s a credit to Reynolds’ writing, that for a book of this size – nearly 700pp of actual narrative – it’s nearly all compulsive reading. If you’ve an interest in the subject Reynolds tells the story well.

Recommended reading to anyone interested in music and social history