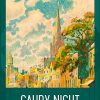

Gaudy Night: the classic Oxford college mystery (Lord Peter Wimsey Series Book 12)

£0.90

The twelfth book in Dorothy L Sayers’ classic Lord Peter Wimsey series, introduced by actress Dame Harriet Mary Walter, DBE – a must-read for fans of Agatha Christie’s Poirot and Margery Allingham’s Campion Mysteries.

‘D. L. Sayers is one of the best detective story writers’ Daily Telegraph

Harriet Vane has never dared to return to her old Oxford college. Now, despite her scandalous life, she has been summoned back . . .

At first she thinks her worst fears have been fulfilled, as she encounters obscene graffiti, poison pen letters and a disgusting effigy when she arrives at sedate Shrewsbury College for the ‘Gaudy’ celebrations.

But soon, Harriet realises that she is not the only target of this murderous malice – and asks Lord Peter Wimsey to help.

‘She brought to the detective novel originality, intelligence, energy and wit.’ P. D. James

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | Hodder & Stoughton (15 Oct. 2009) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| File size | 4374 KB |

| Text-to-Speech | Enabled |

| Enhanced typesetting | Enabled |

| X-Ray | Not Enabled |

| Word Wise | Enabled |

| Sticky notes | On Kindle Scribe |

| Print length | 475 pages |

| Page numbers source ISBN | B0BKPX66B1 |

by Antenna

Her celebrity as a writer of detective fiction gives Harriet Vane the confidence to visit 1930s Oxford for a “Gaudy Night” celebration for the first time since graduating from Shrewsbury College where she was so happy before the trauma of being falsely accused of poisoning her lover and saved from the gallows by the intervention of amateur sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey. When the activities of a poison pen poltergeist begin to threaten the peace and the reputation of the College, Harriet is called back to investigate.

I found this novel entertaining although it proved as dated as I had feared, including in ways I had not expected. In terms of style, it often feels like a novel written a century earlier than it was.The frequent Latin quotations and Greek tags with no translations provided are particularly irritating, but perhaps an educated reader of the time would have had no trouble knowing what they meant. Alternatively, having been taught Latin since the age of six by her father, perhaps Dorothy Sayers overestimated the capacity of her readers, or with the dismissive arrogance often shown by Harriet maybe considered that if they could not understand it they could lump it. There is a similar kind of academic elitism in the often abstruse quotations from sixteenth century writers included at the start of most chapters. Yet the irony is that the female dons of Shrewsbury College frequently behave with the emotional immaturity of the pupils of Enid Blyton’s “Mallory Towers”.

As a detective mystery, the plot is rather thin. This is much more a psychological study of a group of women pursuing careers in a privileged cocoon, yet continually troubled by the sense that they are regarded as inferior to their male counterparts (in separate cocoons) and by doubts as to whether they have made the right choice. Should they have satisfied the desire for a man instead, even at the cost of having to further his career rather than their own, or of sacrificing self-fulfilment to putting their children first? Harriet naturally arouses resentment since she appears to “have it all”: a career in the big wide world, the option to become an academic, and a very wealthy suitor offering her future security for the taking.

For the most part Harriet and Lord Peter (Why does he have to be an aristocrat except to feed some fantasy of the author’s?) communicate for the most part through the exchange of literary quotations and witty ripostes. One of Harriet’s reasons for refusing his regular proposals of marriage seems to be that he makes her feel inferior. With justice, it would seem, in that she has to call him in to solve the crime, and even rewrites her novel to take account of his criticisms of her leading character Wilfred. There is also a double standard in the indulgent attitude to the idleness of Lord Peter’s student nephew, whereas Harriet rages against the “waste” of the place offered to an “ordinary” girl who has only come to Oxford to please her parents.

Many scenes make me uneasy in their elitism: Lord Peter calling a waiter continually to pick up the napkin which has slipped off Harriet’s silk skirt, or Harriet betting in a College sweepstake, not on a horse, but on the student most likely to win a prize.

Despite Dorothy Sayers apparently unconscious snobbery – a product of her times – she sometimes mocks the conventions: the male dons’ ludicrous popping formal shirt-fronts; the pleasure of “snuffing the faint, musty odour of slowly perishing leather” in the Bodleian Library; the possible futility of the complex mechanistic analysis of poetry.

by Marguerite

This was the book I’d been waiting for, reading my way through all eleven previous books in the serious (a mostly positive experience) to reach. At last, Harriet and Peter are going to make a decision about their future together – or apart. But first…

Harriet is having doubts. It’s very, very difficult not to read Harriet in this state as the author being very autobiographical. I know that she actually quit writing the Lord Peter Wimsey series earlier, and only went back to it when her life and fortunes changed. Harriet is doing very well for herself as a writer of detective fiction, but she sees her writing as second-rate, she’s embarrassed by it, and longs for a more literary and academic life. In Oxford, her alma mater, she wonders if this is really possible, and as the story (slowly) unfolds, we see her pondering and debating at length, the issue of academia versus the real world. Can a woman be an academic and a wife? Can she have her own, fulfilled and independent life and at the same time share her life with a man? (Slightly straying from the point here, but this is the debate every one of my own heroines have with themselves in my books, and I know it’s an ongoing debate still, with a great, great many women.)

While Harriet is pondering, and witnessing for herself the hothouse of emotions that accompany the enclosed (almost nun-like) world of the woman’s college in Oxford, there’s of course a crime going on, and this is her excuse to remain there, and to continue to debate her future with herself. The crime – as with most crimes in this series – is secondary to the human interest stories here, the intertwined, often toxic relationships, the pressures on women to conform, or to accept that they will be forever outsiders if they don’t. That issue is in every one of the books, but her it is right at the fore – and it’s enthralling. It’s tedious in some bits, in fact, because it’s so enthralling if you get my drift – the going round in circles, I mean, sounds so familiar, that you want Harriet to get on with it, even though you know that it would be a mistake – huge mistake – for her to just close her ears and jump one way or the other. I was invested to a degree in finding out whodunnit, but most of the time I was simply rooting for Harriet to find a way to have it all. And most of the time, incidentally, Lord Peter himself was very much absent.

This was not flawless. I think it was a little bit too long, a little bit too repetitive. I found the Oxford world a bit toe-curling – no, a lot toe-curling – because I doubt it’s changed that much, and so much oppressive and obvious privilege always makes my wee socialist toes curl. I found the ‘insider’ dialoge, the acronyms and customs, also a bit tedious, and some of the more academic debates also. But nothing that seriously detracted from my enjoyment of this. And nothing that would stop me turning the pages faster and faster.

The ending? Ah, it was perfect. I’ll say no more, but I was doubly delighted to discover that there is another book in the series, and only just stopped myself from diving straight in. But it won’t be long before I do.

by East End Lady

Harriet returns to her old college for an academic celebration and to savour the atmosphere of dedicated academic learning only to find that things are not as peaceful as she remembers.

The academic ladies seem to hold in contempt those who have abandoned them to marry and raise children but they themselves have grown more petty, intolerant and argumentative. There is some unpleasantness with vicious poison pen letters and attacks on college property, which Harriet offers to sort out.

Unfortunately Lord Peter is not available to help her out. He is somewhere in Central Europe trying, by diplomatic means, to avert war breaking out.

We are introduced to his nephew, Lord St-George, the ducal heir, a very beautiful, feckless youth with a reckless attitude to money and fast cars who possesses great charm.

Within the cloistered walls of Shrewsbury College the bickering atmosphere in the senior common room goes from bad to worst .

It is only when Lord Peter returns that there is any hope of resolution.

Harriet gradually realises that she needs him , and that she must have the courage to trust him.

This book is pre-war, and it reflects the mores of the time. The author is enchanted by the erudite elitism .of Oxford, the poetry and ancient customs, and expects that the reader will be too.

She is well aware that her City of Dreaming Spires and the whole of Europe will soon be plunged into war and will be changed for ever,