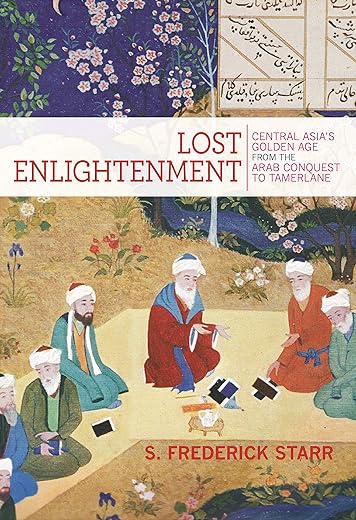

Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane

£17.90

In this sweeping and richly illustrated history, S. Frederick Starr tells the fascinating but largely unknown story of Central Asia’s medieval enlightenment through the eventful lives and astonishing accomplishments of its greatest minds–remarkable figures who built a bridge to the modern world. Because nearly all of these figures wrote in Arabic, they were long assumed to have been Arabs. In fact, they were from Central Asia–drawn from the Persianate and Turkic peoples of a region that today extends from Kazakhstan southward through Afghanistan, and from the easternmost province of Iran through Xinjiang, China. Lost Enlightenment recounts how, between the years 800 and 1200, Central Asia led the world in trade and economic development, the size and sophistication of its cities, the refinement of its arts, and, above all, in the advancement of knowledge in many fields. Central Asians achieved signal breakthroughs in astronomy, mathematics, geology, medicine, chemistry, music, social science, philosophy, and theology, among other subjects. They gave algebra its name, calculated the earth’s diameter with unprecedented precision, wrote the books that later defined European medicine, and penned some of the world’s greatest poetry. One scholar, working in Afghanistan, even predicted the existence of North and South America–five centuries before Columbus. Rarely in history has a more impressive group of polymaths appeared at one place and time. No wonder that their writings influenced European culture from the time of St. Thomas Aquinas down to the scientific revolution, and had a similarly deep impact in India and much of Asia. Lost Enlightenment chronicles this forgotten age of achievement, seeks to explain its rise, and explores the competing theories about the cause of its eventual demise. Informed by the latest scholarship yet written in a lively and accessible style, this is a book that will surprise general readers and specialists alike.

Read more

by Clyde

More detail on philosophy than science, but a very good book

by C.W

This is an excellent book. Very informative and very well written. After having read it, the first thing I felt like doing was reading it again. Very solid and honest scholarship by Starr. World class without a doubt. Definitely the best book I have read so far on the intellectual history of Central Asia, and I can only hope that more people will read it for its potential to sober the prevailing Western view of the region. The book lays out a wonderfully integrated narrative of a highly complex region and its similarly complex intellectual history without neither accusing nor apologizing. It is one of those books that makes you feel truly enriched after having read it, so I hereby give it my strongest recommendation to all with even the remotest interest in the subject. To my mind (and as a professional Historian) this is an example of History writing when it is best.

by Henri IV

He claims, perhaps with reason, that most of what we think of as medieval “Arab” science, philosophy, and general erudition actually belongs to a very different culture, that of the semi-independent Central Asian cities.

by MeMadsen

Brilliantly written from preface to end. About the mid-Asian peoples who translated Greek science (but not Greek Drama) and Indian science and, over four centuries, lead the world in developments in Mathematics, Astronomy, Physical science, Medicine, and Business Development and Administration. Simply enthralling. In the end, it all succumbed to the ‘Strong men’ from outside, like Ghengis Khan, and (closer to home) to the reactionary men of dogma.

Generally, I did not read many pages at a sitting, simply because every page is a gem. Half way through, I wondered when I would loose interest and set this big book aside. But I could NOT put it aside. To – today’s mid-Asian peoples: your antecedents inspire us all; do be sure you know this story.

by Andrew Ross

This is a thoroughly admirable history book, with a persuasive narrative and all the detail in place. The main facts of the story are clear and the verdict is hard to deny — in Central Asia, over several centuries, a cultural and intellectual flowering appeared that bears comparison with the earlier classical flowering in Greece and Rome and the later Renaissance and Enlightenment flowering in Europe. But it died, for reasons that are still debated.

Professor Starr is a distinguished historian with a long record of service to the culture he portrays here, and he may be forgiven for doing it slightly more than justice in this fine history. For although the achievements of the Central Asians in their golden age were impressive and extraordinary, they were not, in the end, in my humble opinion, as astonishing as those of classical Greece or Enlightenment Europe. What was missing was a harder focus on science.

The Persian and Turkish cultures that flowered between the rise of Islam and the Mongol invasions produced remarkable work in astronomy and mathematics. The refinement of the Ptolemaic system with more exact measurements and a more perceptive cosmological perspective prepared the ground for the work of Copernicus, Kepler and Newton. The development of Greek mathematics using Hindu numerals led to great advances in arithmetic and algebra and in what we now call algorithms in homage to Abu Abdallah Muhammad al-Khwarazmi (780—850 CE). But neither advance overshadows the earlier work of Euclid or Ptolemy or the later work of Newton, Euler and Gauss.

Medicine too flourished in the Islamic golden age, but again its achievements pale beside the strides we have made in the last few centuries. As for the philosophy of the era, even as ardent an advocate as Professor Starr admits it was finally all but buried under a crushing weight of Islamic orthodoxy. Altogether the story of the intellect in the golden age was a tragedy, as the religious prejudices of Sunni and Shia fundamentalists not only snuffed out whole traditions of free thought but also banished an interesting religious strand of Sufi mysticism into the darkness.

Central Asia started its golden age with a rich marketplace of religious traditions, including Zoroastrians, Buddhists and Nestorian Christians, but within a century or two of violent struggle the Muslims had gained the ascendancy. Within a few further centuries, their stranglehold had become deadly. When Chinggis Khan and his Mongol hordes descended from the northern steppes and slaughtered all who stood in their way, the culture was already past its best, and with the final bloody conquests in all directions, into Russia, Anatolia, Africa, India and China, of the self-styled “Sword of Islam” Tamerlane or Timur (1336—1405 CE) the Timurid culture broke into the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires, and Central Asia settled into world-historical decline.

Lost Enlightenment is a history book for historians. The reader must make a serious effort to slog through its forest of detail, and I for one would have welcomed more maps, more standing back to take stock and look around more globally, and less special pleading for this or that minor poet or architecturally unremarkable tomb. The Islamic golden age was glorious enough to deserve a central place on the world-historical map, but I think we need to be clear that Islam was at least as much a hindrance as a help to that cultural flowering.

by gingersnapz

This book is a revelation in opening up a new era of civilization and enlightenment of an otherwise relitavely unknown region of the world. If you are the kind of person who likes to have their breadth of knowledge enlarged and world view challenged – this is the book for you. A big yet rewarding read – the author takes you on a journey past the well known characters of Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan and Tamerlane and into the real intellectual heavyweights like Ibn Sina, Al-Buruni, Al-Bukhari and Gazhali (to name only a few) that have changed our society forever. The author goes into enough depth on each topic (that doesn’t leave you too boggled) and offers balanced and thought provoking arguments. This book will leave you feeling more enlightened and wanting to explore more of these wonderful characters in greater depth.

by Henri IV

Considering the subject topic, this is an easy book to read, however it is highly descriptive and any sort of analysis is thin on the ground. The start of the book goes on a bit about warring factions in the area and ensuing change of ruling parties, but this doesn’t really explain anything. A lot of the time there is reference to what was going on in Baghdad, but then the author consistently attributes that innovation to someone who was from Central Asia in the first instance and there the insight ends. There is some reference to the silk corridor, but then thats dismissed as any sort of explanation as to why Central Asia produced individuals who were advanced in their field. The issue is that these themes repeat themselves: its always thanks to Central Asia that science (and in fact the author is partly wrong in describing it as science) and civilisation progressed but does not explain WHY this was so. It becomes tedious because clearly this is a sweeping generalisation and in any case, Central Asia is huge so the point is mostly meaningless anyway. Disappointing as I don’t feel particularly enlightened from having read the book.