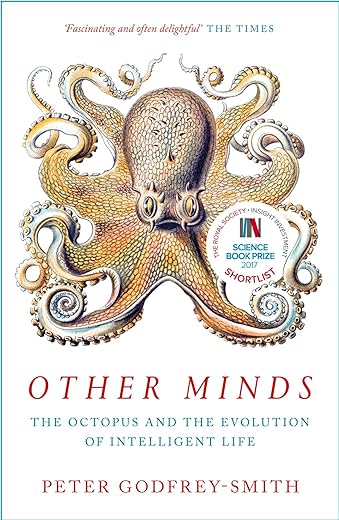

OTHER MINDS: The Octopus and the Evolution of Intelligent Life

£8.50£9.50 (-11%)

BBC R4 Book of the Week

‘Brilliant’ Guardian

‘Fascinating and often delightful’ The Times

What if intelligent life on Earth evolved not once, but twice? The octopus is the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien. What can we learn from the encounter?

In Other Minds, Peter Godfrey-Smith, a distinguished philosopher of science and a skilled scuba diver, tells a bold new story of how nature became aware of itself – a story that largely occurs in the ocean, where animals first appeared.

Tracking the mind’s fitful development from unruly clumps of seaborne cells to the first evolved nervous systems in ancient relatives of jellyfish, he explores the incredible evolutionary journey of the cephalopods, which began as inconspicuous molluscs who would later abandon their shells to rise above the ocean floor, searching for prey and acquiring the greater intelligence needed to do so – a journey completely independent from the route that mammals and birds would later take.

But what kind of intelligence do cephalopods possess? How did the octopus, a solitary creature with little social life, become so smart? What is it like to have eight tentacles that are so packed with neurons that they virtually ‘think for themselves’? By tracing the question of inner life back to its roots and comparing human beings with our most remarkable animal relatives, Godfrey-Smith casts crucial new light on the octopus mind – and on our own.

Peter Godfrey-Smith’s book ‘OTHER MINDS’ was a Sunday Times bestseller w/c 10-05-2021.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | William Collins (8 Mar. 2018) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Paperback | 276 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 9780008226299 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0008226299 |

| Dimensions | 12.9 x 1.75 x 19.8 cm |

by Specky Bob

A great book. Others have already written eloquent reviews, and I can’t better them. My feedback concerns the Kindle edition. Unfortunately, this is not good.

In the printed book, endnotes are referenced by the page numbers and the phrases/sentences to which notes refer. For example, the very first note is added to a sentence, ‘The history of animals has the shape of a tree.’ on page 6. The author doesn’t use note numbers in the main text, so the reader won’t notice the notes to the main text unless they regularly check the notes section. This isn’t necessarily a problem; it keeps the main text clutter-free (unlike some authors, who like to add a note every few lines). But these notes are not hyperlinked in the Kindle edition, so looking for a note is a tiresome affair. With the printed book, you can keep one finger in the notes section, but you can’t do that with Kindle. I wouldn’t have bothered writhing this if the notes only contained bibliographical data and specialised information, but they are interesting, descriptive notes.

I couldn’t have possibly read it and enjoyed it on Kindle. As you will probably have guessed, I bought the printed book as well. The reason I am still giving five stars is because I didn’t want my gripe about the technical issue to affect the review rating, which should be about the content of the book, which is brilliant.

by AZB500

Fascinating book. Thank you.

by Mr. Wol Wallace

Found this book quite absorbing as to the origins, behaviour of octopuses, other cephalopods with the rest of life on this planet and know considerably more than I did about their intriguing species; certainly worth a read noting that the author is a philosopher not a marine scientist so quite an achievement. My only disappointment as such (which NB is relatively minor) is his summary which is somewhat abrupt and an anti climax when would have appreciated something which (acknowledging all the hard work he must have done compiling this study) draws together more emphatically why understanding octopuses is so important.

by Dr T Quin

Let’s get the bad stuff out of the way first. As others have said, Peter Godfrey-Smith doesn’t come across as a particularly good writer, nor philosopher, nor subject-matter expert. The last is certainly unjustified, however you’d probably have got a more enlightening philosophy on the mind and consciousness from your late night cheese and wine (Liebfraumilch?) discussions at university.

But how much do you know about octopuses (or, apparently, octopodes) and cephalopods in general?

The evolutionary tree and time scales are fascinating:

• 4,600 MYA: Earth formed

• 3,600 MYA: First single celled organism (perhaps earlier than this)

• 635 MYA, Ediacaran: Emergence first multicellular organisms and also the bilaterian body plan. Perhaps these animals also had simple light sensitive skin patches. Molluscs, the forbearers of cephalopods, split from rest of evolutionary tree during this period. ie common ancestor for humans and octopodes

• 542 MYA, Cambrian: explosion of body forms we see today

• 320 MYA: Bird and mammal common ancestor. A land dwelling lizard-like animal

• 164 MYA: First uncontroversial octopus fossil

• 6 MYA: Human and chimp common ancestor

• 1 MYA: Homo sapiens

Nervous systems developed independently (although from the same precursor protein), as did eyes. Whereas chordates (including us) have a centralised nervous system, cephalopods have a much more widely distributed nervous system: for instance their arms have enough “intelligence” to act semi-autonomously. Whereas there are many intelligent birds and mammals, cephalopods are the only intelligent molluscs. The common octopus has 500 million neurons, (similar to cats and dogs. This is four orders of magnitude greater than other molluscs ,a garden snail for instance has about 10,000 neurons.

There is an interesting discussion on the purpose of a nervous system. In simple animals it allows animals to do two things: respond to the environment (move toward food or away from pain), and to coordinate the animal’s body. Looking after four feet whilst fleeing a predator is no mean feat. With larger brains animals can start to plan their actions, coordinate within a pack, and solve problems set by animal behaviourists.

Godfrey-Smith then attempts to make inroads into consciousness and self awareness. Without, I feel, much success.

Birds and mammals also demonstrate parallel evolution. Our common ancestor was probably a land reptile that roamed before the dinosaurs. Yet both us (as mammals) and birds have skin covering, are warm blooded, and have developed a level of intelligence. Although anatomically our brains are similar, birds and primates use their brains differently. A raven, as well as having a large brain for its weight, also uses that brain efficiently. The result is a surprisingly clever animal.

Why do cephalopods generate such fascinating skin colour displays? Especially as they’re apparently colour blind, and they are not social.

Another interesting puzzle that Godfrey-Smith raises but doesn’t entirely address: octopuses and cephalopods have comparatively large brains, yet only live for a couple of years. Why do they need such large brains for such a short life span? However the associated discussion on the evolutionary theories of senescence.

The book ends with a polemic on habitat destruction, which is fair enough but off-topic.

So despite the book’s shortcomings, I learnt a lot. Hence a hearty 4 out 5.

by Pinkasfeld

was nice

by Tim Dumble

This highly readable book is a well researched and referenced insight into a fascinating collection of creatures which challenged the hubris of humanity by independently developing intelligence twice.

The remarkable world of the cephalopods is described in a way that sheds light on the evolutionary process and gives context to the geological eras. From the initial development of sensing and moving in single celled creatures to the emergence of the eukaryotes and cooperation between cells the evolution of life in the sea is depicted with clarity and purpose resulting in the most significant random outcome of evolution- sentience in humans and octopuses and maybe cuttlefish.

A personal highlight is the role of predation during the Cambrian era in developing improved nervous systems. Whilst much is speculative, discussion around communication, language, thought and their role in consciousness is fascinating.

You are left with a revised view of the uniqueness of humanity, a respect for the power of evolution and our position within the taxonomy of life. Above all you are beguiled by the outlandish bodies and capabilities of our distant relatives the cephalopods.