Oxford Chinese Dictionary

£34.10£47.50 (-28%)

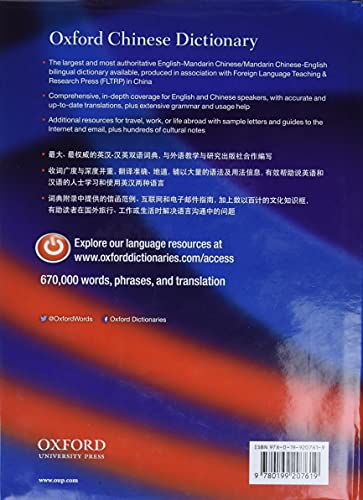

The Oxford Chinese Dictionary contains over 300,000 words and phrases and 370,000 translations, including the latest vocabulary from computing, business, the media, and the arts, and tens of thousands of example phrases illustrating key points of construction and usage. There are over 300 cultural notes giving essential information about many aspects of life and culture in the Chinese- and English-speaking worlds. The dictionary is based throughout on corpus research for both English and Chinese, providing up-to-date evidence on real language. The English is based on the Oxford English Corpus, and the Chinese draws on the LIVAC corpus from the City University of Hong Kong.

Extensive supplementary material includes sample letters and emails, guides to telephoning and text messaging in both Chinese and English, chronologies of Chinese history and culture, and features on particularly difficult aspects of the Chinese language, such as kinship terms and measure words. There are also over 50 pages of lexical and usage notes which contain helpful extra information about Chinese and English.

The organization and layout have been designed for maximum clarity and accessibility. All Chinese headwords and compounds are shown with Pinyin transcriptions, so that the learner of Chinese can pronounce each one correctly. Chinese headwords are given in Simplified Chinese characters, but Traditional Chinese character versions are also given in brackets after the headwords when they differ from the Simplified form. All the English headwords are also shown with phonetics, so that the learner of English can pronounce each one correctly. The Chinese-English section of the dictionary is organised alphabetically by Pinyin and there is also a radical index which allows you to look up a character without knowing its Pinyin form.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | Bilingual edition (9 Sept. 2010), OUP Oxford |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Pocket Book | 2064 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 0199207615 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0199207619 |

| Dimensions | 26.67 x 6.99 x 18.92 cm |

by bigt_lja

I thought it was a pocket dictionary for exam. It was the biggest book I’ve ever seen.

by bertylerty

In general a fine piece of well-coordinated lexicography, bordering on scholarship, but it already has the whiff of a bygone era. It’s got the careful thumbprints of human endeavour all over it (with the occasional error). Eventually this sort of thing will be superseded comprehensively by Google Translate and its ilk. Meanwhile, we’re all still in the phase when translators and lexicographers are appreciated, sometimes, as flesh and blood machines. A bit like the days when grandmasters could beat the best chess computer, on a good day. So enjoy this dictionary for a few years while you can. For when Google Translate finally gets its act together (it will eventually, whether we like it or not) you’ll have to leave this book on the shelf, like a forgotten friend, to gather dust.

Here and there we see a bit of linguistic silliness in its approach (playing to the gallery perhaps?), such as the statement that “Chinese is not a phonetic language” (hmm, what about languages without a script: are they likewise not phonetic?). This gnomic utterance is doubtless just a kind of hand-wringing about the conceptual ghastliness of written Chinese (by ghastly I mean maximally unwieldy, as a system, to be inflicted on Chinese schoolchildren, and foreign learners). Actually the sentence kicks off a perfectly good introductory Guide to Chinese pronunciation. The Guide includes a neat table of mandarin Chinese phonology. Well yes, funnily enough, like all spoken languages, Chinese does boast a phonetic system amenable to rational analysis. Nowadays, the free online versions of that table provide clickable audio as well.

Inevitably, now and again the editor lifts her head at a crucial moment and takes an air shot, for example, on Page 111, 他使我在朋友面前大出洋相 is rendered as “he made a monkey of me before my friends” (meaning in front of my friends). And again on p. 885贻笑大方Yíxiàodàfāng rendered as make a laughing stock of oneself before experts. Let us hope the experts got a couple of laughs when their turn came. 褻龐 is defined as “Favour sb.irreverently…” It might be fun to puzzle over the meaning of that (how would you go about favouring somebody with reverence, for example?) except that, oh whoops…the weird Chinese expression is either vanishingly rare and archaic (i.e. has no place in a single-volume dictionary) or is simply a misprint. On page 768 为难,2nd definition is summarized as 习难 which means learning difficulties, ie innate (internal) difficulties, and a very far cry from the correct definition “make things difficult for” ie difficulties imposed from outside by a deliberately unhelpful person. On p222 敷衍了事的檢討 is translated as perfunctory self-criticism. Ouch, “self-criticism” rather than the word “review”, which would have done the job. Sadly, the spectre of self-criticism carries more than a whiff of the lexicography of the cultural revolution. On page 389, the Chinese verb, derogatory in tone, for “banding people together” is elegantly on display, in the sample sentence: band together a bunch of jobless vagrants to disrupt social order 无业游民,扰乱社会治安. Assuming the lexicographer didn’t just borrow the phrase unthinkingly from an existing mainland dictionary, it is safe to say he or she will not have had in mind the kind of government-sponsored thugs recently seen disrupting demos on the streets of Hong Kong; let alone the glorious origins of the People’s Liberation Army. For decades, Chinese dictionaries carried sample sentences that revealed much about the rhetoric of the great proletarian day: the prissy, hyperconformist, moralistic packaging of everyday malice and stupidity… over which the sadistic concept of self-criticism ruled supreme for several years… Class enemies were牛鬼蛇神 and so on… This dictionary has flushed out most of that awful crap, but evidently not all. Part of the problem was the incredibly rigid and formalistic way the dictionary was fashioned out of its sister publication, the Oxford French-English, English-French dictionary by stripping out the French and substituting Chinese. Lexicographers were obviously not allowed to show initiative if it clashed with the protocol. So the whole enterprise had structure and discipline, but became blind to inconsistencies… and missed opportunities… for example, the word Guilao appears as a derogatory Candonese (sic) word for Caucasians. Now a really interesting text box would have treated borrowings into English from Cantonese, eg gwai-lo by HK expat community.

The translations mostly show the elegance of diction to be expected from a large-scale long-term collaborative project such as this. But sometimes there is a clunkiness that leaves you wondering. On page 932 孕育 gets two meanings. 1st meaning is give birth, 2nd meaning breed, with the example 孕育新思想 rendered rather brutally as “breed new ideas”. That’s ok, the expression does exist, and we do know what’s meant, but “generate new ideas” would have been the proper, genuine British English translation in 2010 (leaving the second headword breed in place, therefore no damage whatsoever to elucidation).

It’s never going to be easy deciding what to include or omit…. But…. take an incredibly common word like, Gun kai滾開, which means “get lost!”, or, less commonly, boiling (water). Amazingly, it is simply not to be found in this dictionary (interestingly, both meanings are to be found in the New Age dictionary published some years earlier), but on the relevant page they did see fit to devote valuable space to “roll a snowball”, and “produce a snowball effect” (guessable shoo-ins insofar as the components in both languages add up very simply in both languages to produce the same concept).

On the same page we find “correct” Chinese characters for Flintshire and Fermanagh. In fact these are to be found in both halves of the dictionary. Well, that’s a relief, we wouldn’t want to render these places haphazardly into Chinese… or what? What is going on here: was our lunch a bit heavy: or could this be a back-door attempt by the British Council to boost tourism by standardizing Romanization of place names? To put this geographical thing into perspective, frequent travellers to China end up learning the names and locations of many Chinese provinces (correctly, one hopes, perhaps even bilingually). This makes sense, especially when each is at least as large as the average European country. Presumably our lexicographers are hoping that visitors to the UK will likewise learn the names and locations of many UK counties (correctly, one hopes, perhaps even bilingually) because they are culturally um, er… oh sod it, because the British Council wanted them listed. (Perhaps with Scottish independence we could enjoy a slightly shorter list of counties, or a longer bout of soul-searching). So it’s three cheers for the lexicographers, and two cheers for the British Council, while we’re at it. Hip, hip.

Meanwhile, the central pages (light grey info pages) are nice, very handy. Also, the text boxes are generally pretty good; one or two are marvels of concision (much better than Wikipedia). Some are rather quaint, such as the one on fengshui. Some text boxes are on topics chosen with a touch of ftang-ftang biscuit barrel logic (after a light lunch?). As “BBC” and “BBC English” get text boxes, so must ITV have at least one text box too. Well yes, of course, for the sake of journalistic balance we couldn’t have billions of Chinese remain in ignorance of the glories of ITV, could we?

Other reviewers have bitterly noted the failure to provide any pinyin whatsoever in the English to Chinese half of book. Also, no pinyin for examples in the Chinese to English half of book. Those editorial decisions clearly amount to a hard-headed assessment that, despite all our globalized rhetoric about the global importance of the Chinese language, those who do actually make the effort to learn it probably don’t count for too much, globally. They won’t buy very many copies of this book, compared to purchases by the billions of Chinese learners of English, nor will they be of interest to the British Council, save for the handful in its employ. Anyway, who needs the practical stuff if they can name all of Scotland’s counties, bilingually?

by David Campbell

I use this dictionary when reading technical (finance) documents in Chinese and for composing simple amendments and other short notes in Chinese. Before buying this I was suffered from frustration at the limitations of the commonly available student dictionaries and the poor quality of online offerings.

For reading Chinese, it is good, with an up to date vocabulary, although not all business terms are included. One minor gripe: the list of characters at the front of the Chinese to English section used in the second step of character look up does not give the pronunciation, which would make finding the character in the next step of the look up slightly faster.

The weak spot in the dictionary is the absence of pin yin in the English- Chinese section. This has the obvious disadvantage to a student of Chinese that one may look up a term, but not be able to say it or type it into a document without first looking up the character in the Chinese-English section.

by Marcin Kijowski

Before I bought this dictionary I had read all the reviews. Most of them are complaints about not including pinyin in English-Chinese part. Of course, they are right(there is no pinyin in E-C part). Because of this many reviewers are disappointed. However, they are wrong and mistaked badly. As it was written in book description: “The Chinese-English section of the dictionary is organised alphabetically by Pinyin and there is also a radical index which allows you to look up a character without knowing its Pinyin form”

we have a radical index, so we do not need in English Chinese part a pinyin included. I checked it with some words and works great. Moreover, I do not agree with the review that the dictionary is not for students: “If you don’t read Chinese well, this dictionary is not for you”. I am beginner in Chinese, (as I have been learning Chinese for a couple of months) and I see that this dictionary is for everyone who knows English at the intermediate level. I examined the dictionary thoroughly and I think everyone who wants to make use of this dictionary should become acquainted with the sections: “Using this dictionary”, “The structure of English-Chinese entries”, “The structure of Chinese-English entries” and “Pinyin and Radical index” sections.

All in all, Oxford did a great work. The item is ” mammoth in size”; many entries and supplements which makes this dictionary at the high level. I would recommend every foreigner who learns Chinese. It is a good offline, paper tool for learning Chinese. It is good for people who wants to give a break away from a computer. The hardcover is a good thing, the dictionary is massive. I think one of the largest Chinese-English dictionary. I highly recommend.