Roll over image to zoom in

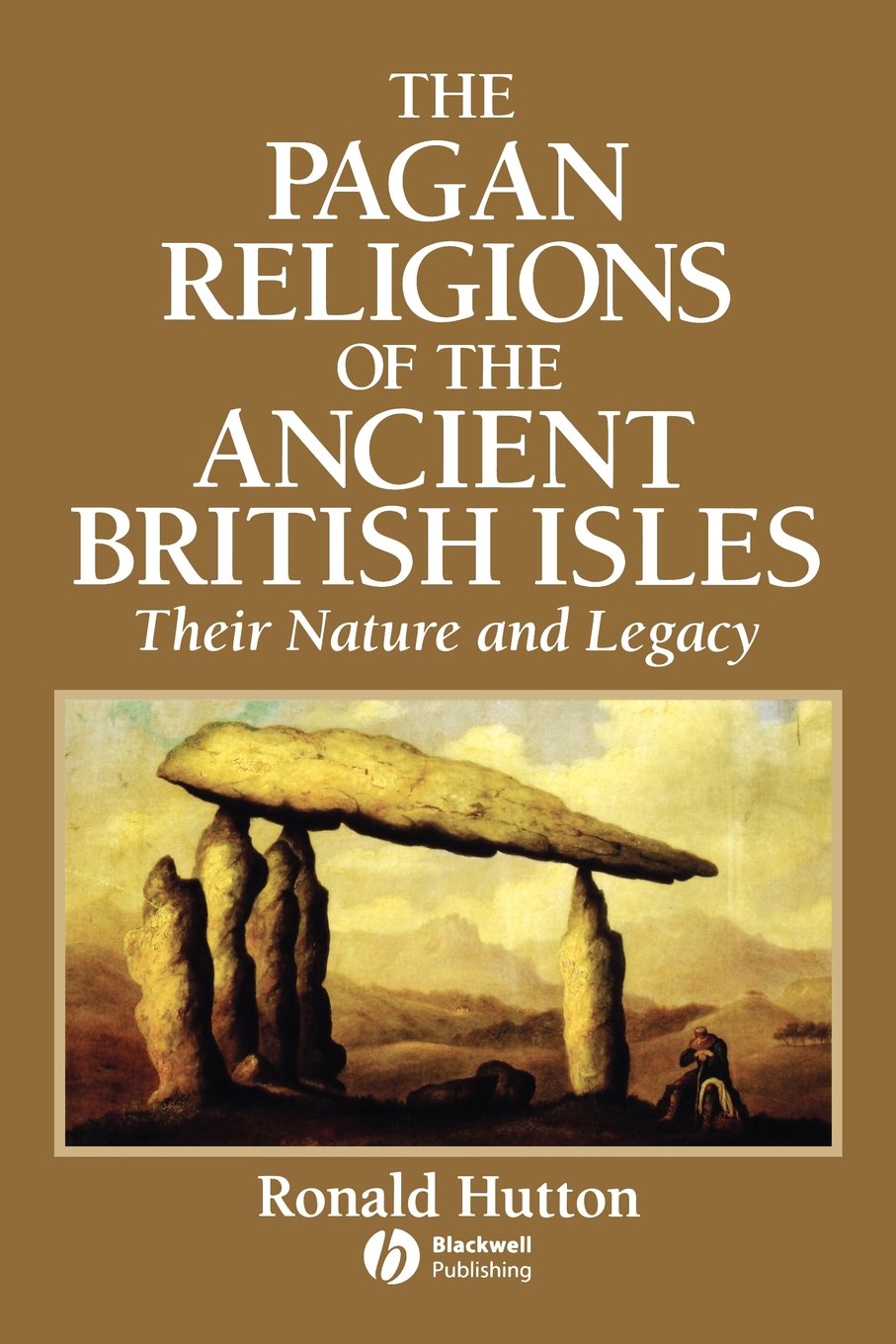

Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy

£32.30

This is the first survey of religious beliefs in the British Isles from the Old Stone Age to the coming of Christianity, one of the least familiar periods in Britain’s history. Ronald Hutton draws upon a wealth of new data, much of it archaeological, that has transformed interpretation over the past decade. Giving more or less equal weight to all periods, from the Neolithic to the Middle Ages, he examines a fascinating range of evidence for Celtic and Romano-British paganism, from burial sites, cairns, megaliths and causeways, to carvings, figurines, jewellery, weapons, votive objects, literary texts and folklore.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | 1st edition (1 Nov. 2010), Wiley |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Paperback | 397 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 0631189467 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0631189466 |

| Dimensions | 15.37 x 2.31 x 22.99 cm |

by Mrs.B. Green

This is a must have for anyone who wishes to read about re Christian /pagan Britain

by Regular Customer

If you were hoping to learn about the ancient religions of Britain or even more how they relate to modern Wicca or Neo-paganism you will be dreadfully disappointed. This is a meticulous and scholarly survey of the archaeological and later historical evidence for the religious beliefs and practices of Britain, and Professor Hutton’s conclusion is that there is nothing we can really know about them. The purposes and motives behind the bewildering array of megalithic structures are open only to pure conjecture. The later historical records of the Romano-British world are almost as unhelpful and H. clearly shows the danger of trying to construct a pan-Celtic religion from the large number of names of divinities found scattered throughout Western Europe.

As a non-Christian, (he was “brought up as a pagan”), H. gives a very fair coverage of the arrival of Christianity to Britain and its rapid triumph, so complete that he finds no possibility for the continuation of any pagan religion.

Particularly interesting is H.’s demolition of modern Wicca and Neo-paganism as having any connection with any ancient faith; not that he has any animosity towards the movement, simply that it is entirely a modern construction which is far more rooted in Magic, itself largely a 19th century construct based on medieval sources – very different to a religion – a difference which he very clearly explains.

My only criticism would perhaps be that H. gives too little credence to vestiges of ancient beliefs in Y Mabinogi, cf. the works of John Koch or earlier W J Gruffydd.

by D. Mackay

Bought as reference book for course, as described and excellent price.

by Wry Nott

I bought this book hoping I would learn something about `the pagan religions of the ancient British Isles’. I did not, other than a few crumbs here or there because at Hutton states on page 341 (the last page) we cannot know anything about them as ‘they perished along time ago and absolutely’. ‘They are lost to us forever’. So there we are, 341 pages saying we cannot know anything – and we – or at least Hutton, does not.

I found this a very irritating book. Hutton appears to enjoy nothing more than demolishing the work of others. His principle target is the neo paganism that has sprung up in the last century, which in his view has no sound basis or lineage. He may be correct but the relish with which he goes about this task is not terribly attractive. He is a demolisher not a builder, which is the weakness of the book. Where he manages to provide content himself, it is mostly in the form of lists of things – like every ancient monument in the UK, or Roman gods. What he does not do is draw any insights from these lists that might shed some light on the answer the title of the book sets out to address. If Tescos can build a world class business by analysing customers shopping lists, I feel a decent scholar ought to be able to achieve a little more than Hutton does with the wealth of material available.

Where he does come across evidence of the persistence of pagan customs he typically rejects it as being unlikely to have survived so long and therefore assumes it to be a recent creation. My recollection is that the Iliad was supposedly passed down by oral tradition for a thousand years, and the Vedas for even longer. Why then is it implausible that we Brits cannot remember through our tales and traditions customs dating back 1500 years?

Hutton makes a distinction between magic – which he does agree has persisted, and religion, which in his view has not, however frankly the difference was lost on me, and comes across as about as useful a piece of academic hair splitting as debating how many angels you can get on a pin head. This does not of course mean that the particular example is not a pagan custom still in use, just that Hutton has not found anything in writing from the pagan past, complete with a date stamp to provide authentication. With such a high requirement of standard of evidence, nothing gets through his filters, and in fact he asserts that the Irish legends are little more than Christian stories as they were originally written down by Christian monks – with that conclusion there is clearly no need to study them further. In a similar vein, all British myths and customs are written off as little more than Greco-roman remnants – therefore again no value no further study. The Norse legends or similarly dispatched. My own recollection of the ancient stories that I have read is that this is not such an obvious conclusion. Nowhere does he provide any detailed arguments for these sweeping generalizations, nor does he go in for the kind of deep forensic analysis and cross referencing from multiple sources that is needed to start to unravel our Pagan past. We are, I assume, supposed to agree with his conclusions because as he frequently points out he is an `academic’ as opposed to the mere amateurs that have dominated the field to date. One is therefore left unsatisfied by this rather shallow book. He does a successful demolition job on a lot of new age nonsense, but does not come up with anything better to replace it. Regrettably I bought two books by him from Amazon – I hope the second is better.

by yellowfish

Love the book arrived in good time very happy

by Stephen A. Haines

It’s easy to envision Hutton tucked away in his Bristol University office wondering if anyone is still reading this book. Published just as the Internet was gaining wide-spread acceptance, it might have forestalled rash of neo-Druidism, Wiccan and other “pagan” cults the Web has fostered. For example, a search in these pages on “wicca”, “pagan” and “druid” returns over 1 400 hits. The “wicca” books may be discounted immediately. Assessing reliable material on “pagan” and “druid” requires close investigation of references – which is the motivation for this book. Hutton insists on reliance on good sources and firm evidence. Modern “pagan” cults have no basis in historical or archaeological data. This work thus becomes a fine discourse on evidence from valid sources and what it can tell us about the people living in ancient Britain. Hutton carefully presents the evidence available from many millennia, declaring, among other things, that local customs far outweighed commonalty of customs.

Hutton’s effort can only be called “sweeping” in scope. Using a chronological structure, he takes us from post-glacial British Isles through the invasion and conquest of the archipelago by Christianity. Early evidence lies in graves and their contents. Hutton shows the diversity of structures, body placement, location and other elements indicates that each community followed its own rules. Most, but not all, were adult males. Body orientation and “grave goods” varied with time and place. Even after Christianization local practices were retained for centuries. How far these practices reached into the past remains unproved in Hutton’s view. Many “traditional” or “ancient” habits of recent decades likely originated in the 17th or 18th Centuries.

While building his picture of data reliability, he’s scathingly critical of those “reading in” the evidence to create false images. The most flagrant of these is the recent “Mother-” or “Earth-Goddess” contrived by Marija Gimbutas and her adherents. Gimbutas finds “divinity” in nearly every artefact – “Venus” statuettes, painted images, carvings on bone. Hutton is more discerning, arguing that we might view the Venus figurines as dolls or invocation to household spirits. They are not, he contends, justifiably viewed as representing a single deity, nor even necessarily a deity at all. He applies this skeptical view to a number of other widely-held suppositions, asserting that what is claimed must be proven. That Gimbutas’ unfounded claims for divinities have spread widely, even into university curricula, is sad testimony to the lack of attention Hutton’s work has received.

Hutton is, in one sense, far too gentle in his approach in discounting the works of those misreading or inventing evidence. He asks for validation of claims where he could be directly contending with claimants. He has far too much respect for those who don’t deserve it. He acknowledges, for example, that Robert Graves’ “Triple Goddess” was an invention – as did Graves – but neither has quelled the ensuing adoration of the idea by a credulous public. Hutton also suffers from production cost woes. The illustrations in this book are nearly all line drawings of carvings, implements and figurines. While they illustrate his points, they are devoid of environment, leaving you wondering what else might be brought into the interpretation. There are some reproductions of paintings which strive for accuracy, but they are mostly indistinct. These illustrations are designed to convey the most likely cultural scenarios, but don’t contribute to Hutton’s presentation significantly. They can all be generally ignored, leaving the reader to concentrate on Hutton’s presentation, which is admirable. If his efforts produce more excavations and research where these are lacking, then perhaps this book will have accomplished its aim. His writing is clear even where the evidence is not. Perhaps some of those taking this up will carry on the work to clarify what is missing. [stephen a. haines – Ottawa, Canada]