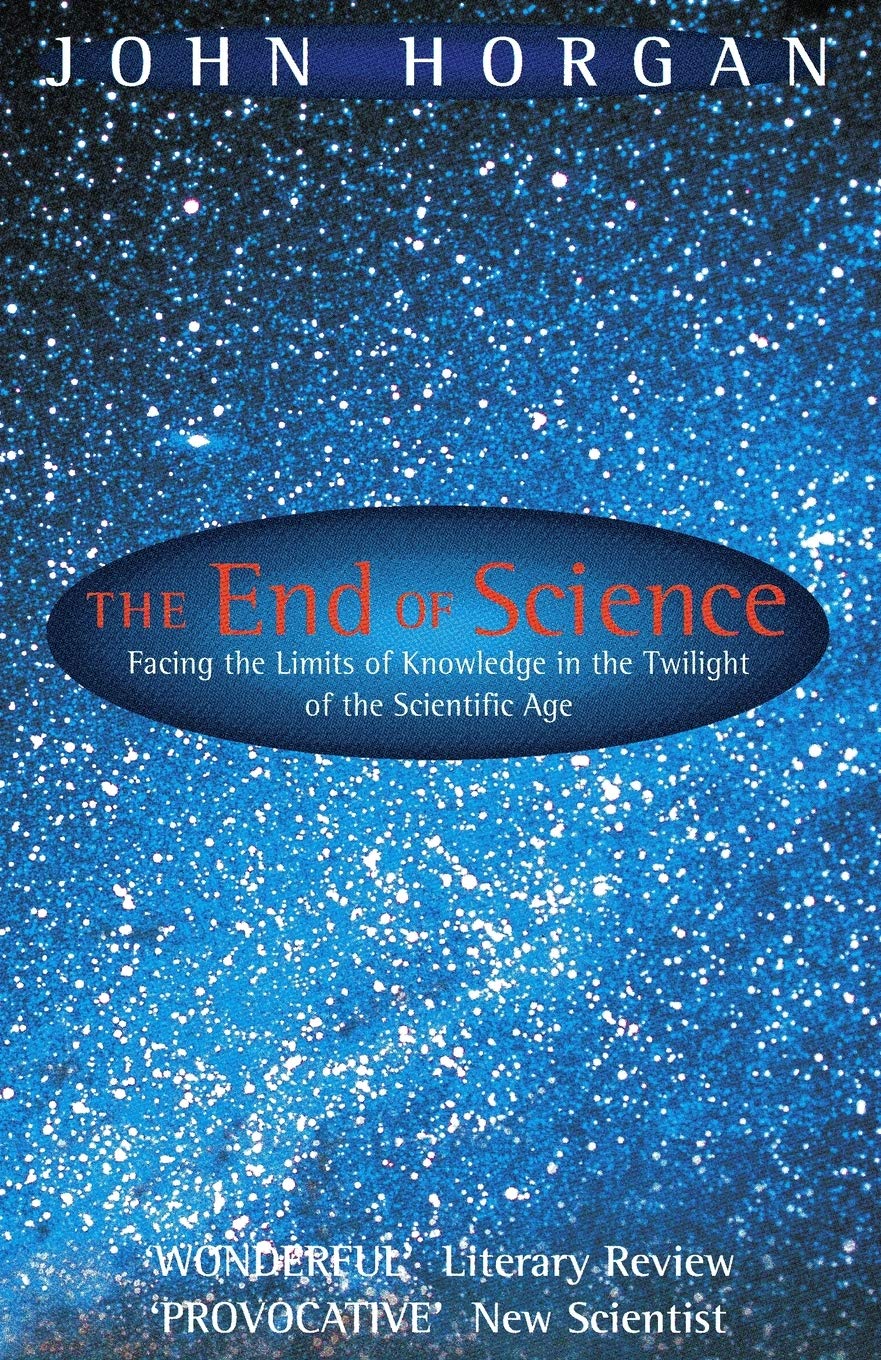

The End Of Science: Facing The Limits Of Knowledge In The Twilight Of The Scientific Age

£10.40

As a writer for SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, John Horgan has an unsurpassed window on contemporary science, routinely interviewing the scientific geniuses of our times, scientists such as Richard Dawkins, Murray Gell-Mann, Stephen Hawking, Karl Popper and Noam Chomsky. In THE END OF SCIENCE, Horgan displays his genius for getting these larger-than-life figures to be human, whilst also encouraging them to confront the very limits of knowledge. Have the big questions all been answered? Has all the knowledge worth pursuing become known? Will there be a final ‘theory of everything’ that signals the end? Horgan extracts surprisingly candid answers to these and other delicate questions as he discusses God, Star Trek, superstrings, quarks, consciousness and numerous other topics. In a time where scientific rationality is under fire from every quarter, THE END OF SCIENCE is a witty, thoughtful, profound and entertaining narrative which serves as both a critique of and a homage to modern science.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | Abacus (5 Mar. 1998) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Paperback | 338 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 0349109265 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0349109268 |

| Dimensions | 12.9 x 1.96 x 19.8 cm |

by carlo sansolo

While transhumanists are spreading the creed of augmenting returns for every discovery John Horgan is stating the opposite, there will be dimiminishing returns and most fundamental discoveries have been made. That is his view. He may be very wrong, let’s watch out for the next twenty years, but superficially he is right.

by Brian R. Martin

Speculating about the future of science, and even whether it has a future, has a long history. Modern interest has often focused on particle physics and cosmology; because these areas are already facing a crisis in how to test their latest theories (such as string theories and inflation) because the energies needed to do so appear to be well beyond what can ever be attained in practice. Questions have also been asked about whether some theories, such as the existence of multiple universes are even testable in principle. (Horgan calls such theories `ironic science’, i.e. theories that are not possible to verify experimentally, in principle or at least within some foreseeable time frame.) But other branches of science are not immune from such criticism and Horgan’s book is a modern attempt to address the question in the context of science as a whole, and knowledge in general. It consists of discussions with leading scientists and thinkers across a range of disciplines. The range of interviewees is very impressive, and contains many of the leading figures in several diverse fields.

The discussions are not reproduced verbatim, but are edited by Horgan, with some direct quotes. We are therefore reliant on his accurate portrayal of the views of the interviewees, and some commentators (the Nobel prize winning physicist Philip Anderson, for example) have questioned whether Horgan has slanted them with an anti-scientific bias. I see no obvious evidence of this, but it is hard to prove one way or the other. We will probably never know. Because the book was first published in 1996, it is interesting to see how the views and predictions made then have stood the test of time. On the pessimistic side, inflation was considered with suspicion by many cosmologists, but is now mainstream; others expressed doubts about the possibility of ever refining the value of Hubble’s constant, and hence our knowledge of the age of the universe; another leading cosmologist expressed the view that the late 1980s and early 1990s would be seen as the golden age of cosmology, and in the future would become like botany – a vast collection of empirical facts loosely bound by theory. On the other hand, one famous cosmologists was even `willing to bet’ that the proposer of inflation, would receive a Nobel Prize before the start of the millennium (i.e. 2000), and several leading physicists confidently predicted that string theory would be experimentally tested `within a decade’. It is a sobering thought that none of these views and predictions has come true.

The other fields that are considered, evolutionary biology, neuroscience, social science, and machine intelligence, have not yet hit an intellectual `wall of doubt’ in quite the same way, although even here there are mixed views as to whether knowledge will ultimately be limited. For example can we ever understand consciousness; Crick for one is firmly in the camp that believes the scientific method will eventually solve even this problem. Some of the most interesting, although pessimistic, discussions are in the chapters on chaoplexity (the amalgam of chaos and complexity theories) and machine intelligence. Once considered some of the most exciting fields of research, they have not matched their early promise of applicability to a wide range of apparently dissimilar problems and generally seem to have `run out of steam’. Even the Director of the leading chaoplexity institute, the Santa Fe Institute, is pessimistic that the field will produce anything truly fundamental.

I enjoyed this book. Although it is not without errors of fact, it is a thought-provoking read. It is true that like much of the `ironic science’ he describes, his views are themselves often incapable of being verified, but I do not agree with some critics that Horgan is promoting antiscience, the rising tide of irrationality and hostility towards science. His message, that `belief in the eternality of progress is the dominant delusion of our society’, is one worthy of serious consideration, even it is eventually rejected. The book is well written and not without humour – the description of a conference in the chapter on the End of Limitology is hilarious, almost a parody of an academic conference – and the descriptions of the interviewees themselves are interesting from a human point of view. They often `expose’ a side that is not apparent from their discoveries and public pronouncements.

by Simon Knows Nothing

John Horgan starts well by talking to Thomas Kuhn and Feyerabend, questioning the way science ‘proceeds’ (he misses Pauli’s quote that ‘science proceeds one great funeral at a time’), but then Horgan gets totally and utterly lost trying to understand the problems in Quantum Theory & Consciousness. Horgan does just the wrong thing. He interviews ‘great men’ who happened to have made a big discovery and then gone totally doolally. Stephen J Gould’s ideas are bogus and inspired by Marx. Fred Hoyle lost the plot after not getting a Nobel. The list goes on. Horgan can’t see that most of these guys picked the wrong path at some point in their careers, and being totally obstinate (which is why they made their names in the first place) ,just keep going in their obsessions. As such the book is profoundly anti scientific and Horgan reminds me of Carl Sagan’s prophesy.

“I have a foreboding of an America in my children’s or grandchildren’s time — when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what’s true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness…”