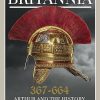

The Long War for Britannia 367–664: Arthur and the History of Post-Roman Britain

£2.80

This history of early medieval Britain sheds light on the real King Arthur and settles longstanding historical misconceptions about the period.

The Long War for Britannia examines some two centuries of ‘lost’ British history, while providing decisive proof that the early records of the time are far more reliable than many scholars believe. Historian Edwin Pace also demonstrates that King Arthur and Uther Pendragon are the very opposite of medieval fantasy—even if different British regions had very different memories of these post-Roman British rulers.

Some remembered Arthur as the ‘Proud Tyrant’, a monarch who plunged the island into civil war. Others recalled him as the British general who saved Britain when all seemed lost. The deeds of Uther Pendragon replicate the victories of the dread Mercian king Penda. Pace demonstrates how these authentic—yet radically different—narratives have distorted the historical record in way that persist today.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | Pen & Sword Military (8 Dec. 2021) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| File size | 8266 KB |

| Text-to-Speech | Enabled |

| Screen Reader | Supported |

| Enhanced typesetting | Enabled |

| X-Ray | Enabled |

| Word Wise | Enabled |

| Sticky notes | On Kindle Scribe |

| Print length | 388 pages |

by Hereward the Wakeful

Because I’ve read a few books on the subject on King Arthur it doesn’t make me an expert but as far as I’m concerned this book kicks all the others into the long grass. The scholarship and research are profound and the argument persuasive and logical. Assumptions are strictly avoided, and everything is based on clearly outlined evidence. Maybe I don’t know enough to challenge any of the argument but it all sounds good to me. If there is any book you need to read about post-Roman Britain and the kernel of historicity about Arthur it is this one.

As a side note I was finally gratified to see some mention of the Frisians instead of just the usual Angles, Saxons and Jutes. I have always been puzzled why they figure so little or mostly not at all in histories of formerly Dark Age Britain. That puzzlement began many, many years ago whilst I was in that part of the Netherlands that is still called Frisia. At a rest stop whilst happily chugging on my coffee three locals were chatting at the counter and I was close enough for their conversation to drift into my ears. The reason I picked it up was because I could understand quite a lot of it. It could be no coincidence that this local dialect, regional language or whatever you might call it, was so close to English. Why had I never heard of this connection before? I knew there had to be one but I’d never seen it even mentioned in any history books – and I am a very serious reader of history books! How has everyone missed this? Or maybe they haven’t and somehow I’m the one that has missed the tomes on the history of the English language that examine this connection. And I’ve read quite a few of those too!

by M Harold Page

This is a good rich read for history nerds.*

It’s a mix of engaging narrative and well-argued reconstruction, with interludes in which he shows his working as he unravels mangled dating systems and parallel narratives. His military background shines through, illuminating the era: He understands war, culture and economics. There’s also a kind of antiquarian coda in which he finds traces of real history in Geoffrey of Monmouth, and speculates about sources.

(Note that this is not really about King Arthur: Pace comes to what should be a conclusion that’s obvious as soon as it’s pointed out, reconstructs that phase in a chapter or so, and moves on with a narrative informed by that conclusion.)

Alas, for all the author’s scholarly credentials – he has peer reviewed papers in academic journals – this is written as a popular narrative history, so I doubt this will be the new orthodoxy.

However, for aspiring authors of Historic Fiction and tabletop roleplayers and wargamers looking to do historical campaigns, this is pretty much the holy grail: the most plausible and exciting joining of the dots, just put imaginative boots in the ground.

And, it was great to put on Hans Zimmer’s Gladiator soundtrack and hang out with the old gang – Gildas, Geoffrey Nennius and the rest – while contemplating the shooting stars of Roman Britain’s long twilight.

*MORE DETAIL

Pace derives his narrative by (a) using linguistic evidence and very plausible dating system corrections to show that disparate sources actually record the same events and people, thus resolving the mess into a handful of dots with only a few possible ways to join them, (b) framing this in the context of modern archaeological discoveries, continental Late Roman/Early Medieval history and sources, an appreciation of the theology and religious imagery of the time, and serious consideration of plague and environmental disaster, and (c) comes to conclusions based on a realistic appreciation of logistics, economy, warfare, and personal agency.

The end result feels about right to me because it discards British exceptionalism, presents a Britain not so different from post-Roman Gaul, and just as messy, but on a different path, and assumes the major players are acting rationally, but within the framework of their culture.

I also like that the conclusions are pretty much hidden in plain sight.

by JP

This is an excellent book, an immense amount of work and thought has gone into it and it should become accepted as the standard.

There are, though, two minor points that I would like to make that should not affect the five stars I think the book is worth.

One is that, as the chapters are full of information and names, I would have appreciated a summary paragraph at the end of each one. Useful for the older reader.

The other is that the book fails to convey any feeling of the horror of ‘ethnic cleansing’.

That there was serious ethnic cleansing cannot be doubted. Recent surveys of DNA (‘Britain’s DNA Journey’ by A Moffat) have shown how the Celtic British were replaced by Anglo-Saxons. This book accepts that, but states that the process was ‘irenic’, ie carried out peacefully. That would have been impossible.

After three and a half centuries of peace under the Romans, all reasonable farming land would have been occupied by British farms. For a peacefull occupation The Saxons would have had to turn up driving their cattle and pigs and dragging waggons carrying their poultry, seeds and tools. They would also have had to bring enough food to last till their farms became productive, even though they would have been farming the poor land that the Brits did not want. This, of course, is fantasy . The Saxons came with nothing but their weapons and their families. If they wanted a farm they took over a British one, and if the farmer resisted, too bad!

Naturally the Brits did resist, which is why the conquest took such a long time. The nature of the British farming communities is a little vague, but the standard pattern of Saxon villages is well known. They were built round the hall where the headman lives with his household troop (think Beowulf), ready to turn out if the village was attacked. The fields were grouped round the village and collectively farmed to keep the population close. It can be seen that these villages were organised for defence as the Saxons knew they had to fight for their land.

The conquest proceeded in fits and starts as the balance of population changed, and it was permanent in the way that the Roman and Norman conquests were not. It was horrible, and anyone considering the nature of ethnic cleansing could do worse that read ‘The IRA and Its Enemies’, by Peter Hart, particularly Chapter 12.

All this might seem like a bit of a rant, but horror and hatred are a part of history and should not be ignored.