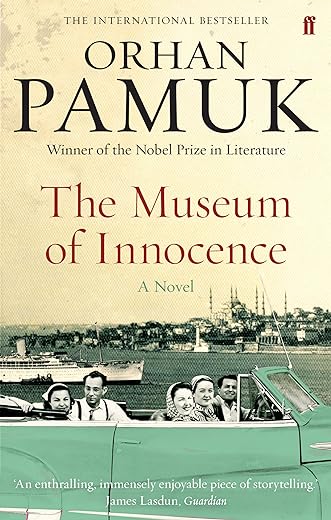

The Museum of Innocence: A Novel

£9.60£10.40 (-8%)

A deeply moving portrait of a torturous love affair that shows Istanbul in all its complex beauty.

** ORDER NIGHTS OF PLAGUE, THE NEW NOVEL FROM ORHAN PAMUK **

Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature

‘An enthralling, immensely enjoyable piece of storytelling. . . a very tender evocation of Istanbul’s moment of dolce vita.’ – The Guardian

‘Intimate and nuanced.. A classic, spacious love story.’ – Pico Iyer, The New York Review of Books

Kamal lives a life of cosmopolitan glamour, exploring the restaurants and boutiques of Istanbul with his friends and fiancé. In the newly modern city, they pride themselves on their liberal attitudes and Western style.

A chance encounter with Fusun, a working-class shop-girl, begins a long, obsessive love affair, one that draws him deep into Istanbul’s complex history, and uncovers the forces of class and gender that still control its inhabitants’ lives.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | Faber & Faber, Main edition (2 Sept. 2010) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Paperback | 752 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 0571237029 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0571237029 |

| Dimensions | 12.6 x 4.5 x 19.8 cm |

by JuliaC

This was my first experience of Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk’s work, ventured into after reading glowing reviews in the weekend broadsheets. And what an enthralling and utterly enchanting experience it was. It is the story of rich Turkish playboy Kemal, and his accidental and ultimately all consuming love for his distant cousin Fusun. It is also a fabulously rich description of Istanbul from 1975, and the world that Kemal inhabits, which springs to life from the pages of this book.

He is 30 years old and on an established and respectable course to marriage with an equally well off and respectable woman, Sibel, whom his family and friends totally approve of and expect him to settle down with. But on route to buy Sibel a present, he comes across his beautiful young distant cousin Fusun, and their three lives are never the same. The way that Pamuk, and indirectly his brilliant translator Maureen Freely, lets this tale unfold is so loving and rich and romantic, that it is somewhat surprising coming from a male writer.

Kemal is unusually expressive, and given to living by his heart rather than his head, and what a big heart he has. At first he seems to be wending the familiar path of having his cake and eating it, as he refuses to think that he needs to change anything about his relationship with his girlfriend, soon to be fiancé, Sibel, whilst falling head over heels in love in an all consuming fashion with Fusun.

In hindsight, Kemal, as the narrator of the story, admits that `no one recognizes the happiest moment of their lives as they are living it.’ And as he and Fusun spend many an idyllic, erotically charged hour in his family’s spare and unused apartment, he is not aware of how much she really means to him. But Pamuk does not let us simply despise Kemal as a selfish man who wants a beautiful mistress and a respectable wife too. We soon are drawn into Kemal’s world, with all his weakness and failings on show for all to see.

The class difference between Fusun and Kemal is an obvious barrier that he does not want to confront. The position of women in the Turkish society of the day is highlighted in fascinating detail as Kemal strips both Fusun and Sibel of their virginity without marrying either – a very serious breach of the accepted societal norms of his culture and time. The limitations put upon women and what they are and are not allowed to do is one of the themes at the heart of the novel.

Without giving away the plot, suffice it to say that the course of Kemal’s love for Fusun does not run smoothly. He descends into an obsession with her, and all things and people related to her, that results in a mania for collecting objects that draw him ever closer to her – eventually to make up the museum of the book’s title. In the ends he is paralysed by his feelings for her – unable to realise them in full, and unable to move on with his life.

Pamuk has written a beautiful and gripping story. It is so full of minute and engrossing details that it is hard to describe or explain how lovingly and engagingly he lures the reader in. As he himself says at one point, the `purpose of a novel … is to relate our memories with such sincerity as to transform individual happiness into happiness that all can share.’ At times it is more like unhappiness that Pamuk is sharing in this book, but he definitely had this reader hooked, and hungry to read much more from him.

by Mr. D. James

Orhan Pamuk,

The Museum of Innocence

It is both easy and difficult to talk about this intriguing novel by the recent Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature – a prize of course awarded for lifetime achievement rather than for a particular book. The easy part is to tell the plot, which usually in my experience takes up at least half of a review. The difficult part is to convey the quality of one’s reading experience. So, to the plot, briefly:

Kemal, who tells the story – later we discover his story is ghost-written by a friend – is a wealthy businessman who falls in love with a poor shopgirl, one who has recently come third in a beauty contest. Unfortunately, he is engaged to an aristocratic girl to whom marriage for familial and business reasons would be more suitable. So far, so trite, but this is not Jane Austen all over again; this is romance, writ large to the nth degree. For Kemal is an obsessive; he not only cannot detach himself from Füsan the shopgirl, but can think of nothing else. All through the period of his engagement and, later, his marriage to Sibel, Kemal collects memorabilia associated with his beloved. This collection of sacred relics begins with a lost ear-ring and ends with a museum.

What is remarkable about this everyday story of an infatuated lover is the revelation of an interior world, where recalled scenes and images are as life-sustaining as the memorabilia he treasures. Cigarette butts with Füsan’s lipstick on and stolen kitchen equipment are but two of the thousands of his objets d’art. Each item brings back a time and place where he loved and suffered in the past. He polishes them or kisses them in his mother’s apartment where he sets up his shrine. His fling with Füsan took but a short time, but it remains with him for life. Of course, he occasionally asks himself what good this `love’ does him or anyone else. The answer is not a scrap – the reverse in fact. But he can’t help himself; the drug will never leave his system, and if it did do so by a miracle, the reader feels the poor man would not survive.

The claustrophobic setting is Istanbul in the 1970s and beyond. The streets are narrow and crowded and the heat suffocating. Kemal names every street along which he has passed, dreaming of the beloved or remembering his later suffering. He presents the reader with a map, highlighting important features, and, to complete his encyclopaedia of folly he appends to a 700+ page novel a paginated index of all the characters mentioned.

What I loved most about this Proustian novel was the privileged view I was given of another consciousness, a madman one might say, a self-destructive obsessive, one who sacrifices everything for a dream, a no doubt selfish illusion about a fairly unexceptional girl. Except that we are made to realise that nobody is unexceptional, that the other characters whom Kemal damages are alive and immortalised in the book, just as his treasures are enshrined in his museum. We feel sympathy for them, even those who are hostile to him.