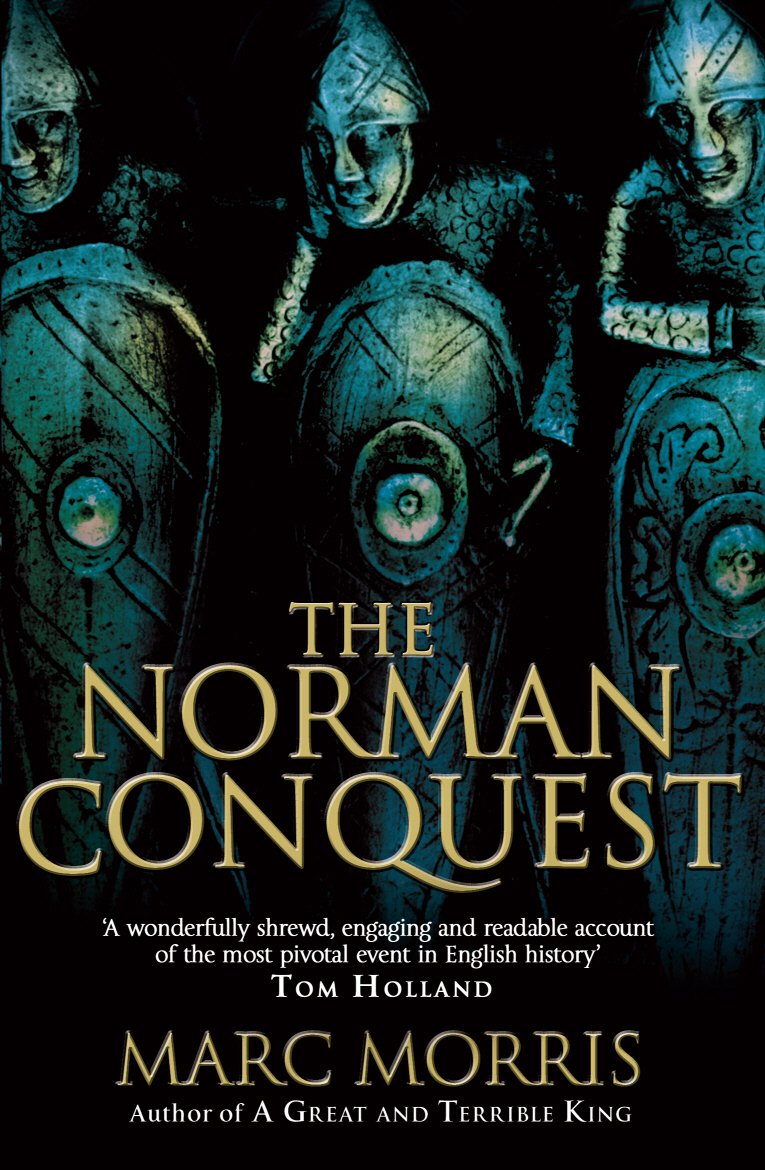

The Norman Conquest

£10.80£12.30 (-12%)

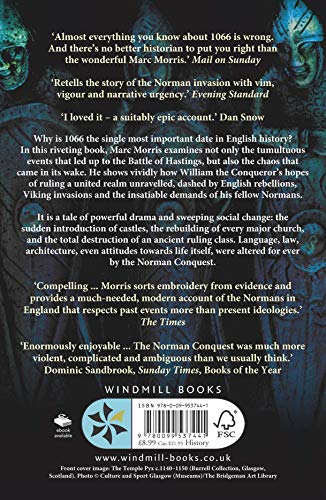

An upstart French duke who sets out to conquer the most powerful and unified kingdom in Christendom. An invasion force on a scale not seen since the days of the Romans. One of the bloodiest and most decisive battles ever fought. This riveting book explains why the Norman Conquest was the single most important event in English history.

Assessing the original evidence at every turn, Marc Morris goes beyond the familiar outline to explain why England was at once so powerful and yet so vulnerable to William the Conqueror’s attack. Why the Normans, in some respects less sophisticated, possessed the military cutting edge. How William’s hopes of a united Anglo-Norman realm unravelled, dashed by English rebellions, Viking invasions and the insatiable demands of his fellow conquerors. This is a tale of powerful drama, repression and seismic social change: the Battle of Hastings itself and the violent ‘Harrying of the North’; the sudden introduction of castles and the wholesale rebuilding of every major church; the total destruction of an ancient ruling class. Language, law, architecture, even attitudes towards life itself were altered forever by the coming of the Normans.

Marc Morris, author of the bestselling biography of Edward I, A Great and Terrible King, approaches the Conquest with the same passion, verve and scrupulous concern for historical accuracy. This is the definitive account for our times of an extraordinary story, a pivotal moment in the shaping of the English nation.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | Windmill Books, Reprint edition (7 Mar. 2013) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Paperback | 464 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 0099537443 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0099537441 |

| Dimensions | 12.93 x 3.56 x 19.76 cm |

by JPS

This perhaps one of the best books – and certainly one of the best ones – for someone who is looking for a comprehensive overview of the Norman Conquest of England. While written in an engaging style for the so-called “general reader”, it is also an excellent starting point for whoever intends to “get more involved” with the various and multiple aspects related to the Conquest.

While, as a biography, it may not be as good as Douglas’ or David Bates’ biographies of William the Conqueror, it is more recent and therefore more up to date. It does however contain many elements of the Conqueror’s life, post pre and post Conquest, since this is both necessary and unavoidable to understand the events, and in particular William’s determination and relentlessness. Among the most up to dates elements are the developments related to the so-called Bayeux Tapestry (with which the book begins), but also assessments drawn from scholarly studies of the Domesday Survey and the Domesday Books (the plural is intentional as you will find out when reading the book) on the impact of the Norman Conquest on the society of the invaded and occupied country.

The author does make, as another reviewer has already mentioned, an excellent job of using, interpreting and reconciling the primary sources, including charters. He also, and just as importantly, has a talent for synthetizing and summarising in an entertaining way the huge amount of secondary sources.

This, for instance, allows Marc Morris to include some useful developments of the Normans in Normandy and the origins and history of the Duchy before 1066, which are partly drawn from David Bates’ works. Also included is a fair amount of context with regards to the Kingdom of England from Ethelred onwards and including the Danish (very hostile) take-over and the whole reign of Edward the Confessor. The point here is that more than a hundred pages of context are provided to the reader. Also included is an up to date bibliography which runs some sixteen pages. Abundant endnotes accompany each chapter and contain more references to both primary and secondary sources. Also worth mentioning are two good maps of England and Normandy and two good family trees of the English and the Norman families and their respective connexions, although they have been somewhat simplified and do not include all members (and in particular not all female members).

Another core strength of this book is the author’s care (and sometimes humour) when presenting and avoiding the biases contained in the sources. Contrary to another reviewer, I did not find any instances when the author himself expressed any bias. I also tended to find his explanations rather and often very convincing, including his analysis of the conflicting narratives of the death of Harold who, contrary to the official version, seems to have targeted by what was the equivalent of a death squad towards the end of the battle for reasons that the author presents rather clearly. Interestingly, some fifteen years later, Norman knights would try (and fail) doing something very similar at the battle of Dyrrachium against the Alexis Komnene, the byzantine Emperor.

While what constitutes the second part of the book includes the events of the year 1066, the last part of the part carries the story down to the death of the Conqueror while the last chapter includes an assessment and considerations on the aftermath down to the loss of Normandy and of most of the Plantagenet possessions in France. Here again, Marc Morris draws on a wide range of existing and more specialised books but he does so seamlessly without at any time giving the impression that his own work is a compilation and while keeping up the reader’s interest (or, at least, this reader’s interest!) at all times. Here again, he manages to deliver a well-informed, entertaining and very dramatic story while also making all the main points clearly. As already mentioned by another review, there is nothing ground breaking or even new in this book. However, there is just about everything we do know currently on the subject and it is offered in a very accessible way. All of this makes this book clearly worth five stars.

by Mr. S. J. Isserlis

Riveting read. A detailed and well supported account of the foundation of modern England.

Plus ca change, plus c’est le meme!

by Ian Thumwood

Although I have read and enjoyed Marc Morris’s other history books, I had been hesitant to read this one because I had read so much about the Norman Conquest both as an A level history student and also when I rekindled my interest in this period of history back in the early 1990’s. On top of this, my interest in this period had seen me explore many of the relevant sites in Normandy. Over the years, I had read so many books about 1066 that I felt there was nothing new to learn.

I therefore would have to say that, in a crowded and competitive market, Marc Morris has delivered the most thorough and lucid account of the Norman Conquest I have encountered. If anyone is new to this topic or wants to explore the subject beyond what they learned at school, Morris has delivered an account which delves back in to the unsettled politics of the 11th century to conjure up a vivid picture of the time which puts King Harold and William the conqueror in their true context whilst also looking at rather shaky political world in which William grew up. Other historians have explained the broader context of the period in England and Morris is not unique in going back to the reign of Cnut to explain the times. Pick up any French guide books from sites in Normandy and the picture offered by Morris can also be found there. Although the combination of these two strands provides an interesting narrative and offers a balanced perspective of the invasion that does serve as a “one stop shop” , I feel that Morris exceeds a lot of other writers by his account of the post-invasion world.

Oddly, the account of the battle of Hastings is not dwelt over too long and this battle is not really given any greater attention than Harold’s earlier victory against the Vikings at Stamford Bridge. Where the book gets really interesting is the analysis as to why any invasion with much as relatively small force proved to be so successful and why the English resistance was so ineffectual. This is something that I feel many other historians gloss over and Morris’s decision to record this in detail certainly covers a lot of new ground that I have never encountered in other histories. I also like the fact that this author looks at his sources such as Oderic Vitalis and manages to put each account in it’s own political context so that the reader is able to separate Saxon spin from Norman spin! It is fair to say that elements of the conquest such as the implementation of the feudal system and the Domesday Book tick the A level Economic history boxes but Morris offers a different spin, approaching these topics to look at the social and political aspect so that the reasons for the absence of English landowners is given as much attention as the Norman’s gradual abolition of slavery , a over-looked fact of Saxon life.

It is true that this book might be considered “populist” yet Morris is a good and rigorous historian. I don’t agree with some reviewers suggesting he is pro-William but I feel that he is rightly critical of the ineffectual Saxon opposition. I would concur that the problems the Saxon aristocracy and clergy faced post-Conquest had a lot to do with their immediate actions post-Conquest. William’s original intention was work with his Saxon subjects as was attested by the English witnesses to his coronation. In this book, you can gradually see how the political ambitions of the Saxon aristocracy and the greed of the mercenary Normans forced William in to the situation that had evolved by the time of the Domesday Book. Too many historians treat this as a fait accompli yet Morris , in ploughing through the detail of Saxon resistance, comes up with an entirely fresh and fascinating alternative. As good as the first half of the book is, the second , post-Conquest section is hugely compelling because the author addresses some questions that I have had for years about the Conquest and, despite being a topic I felt I had read everything I could possibly know, Morris looks at other Norman campaigns in places like London, Exeter , the Fens and Dover which have been overlooked by others. In his introduction, Marc Morris explains that he felt that too may historians of this period have kept “the best bit of this story to themselves.” Having finished the book , you realise just how poorly so many historians have been in covering the period 1066-1086.

For my money, this is the “go to” account of this period and if , like me, you secretly wish that the story might have a different ending with Harold victorious, Morris has written some very readable books about Medieval history in the past but I would have to say that he deserves a massive amount of credit for considering the invasion in far more details than any other historian. This is the best book I have read on this subject and a “must read” for anyone interested in English history.