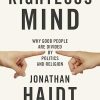

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion

£11.10£12.30 (-10%)

‘A landmark contribution to humanity’s understanding of itself’ The New York Times

Why can it sometimes feel as though half the population is living in a different moral universe? Why do ideas such as ‘fairness’ and ‘freedom’ mean such different things to different people? Why is it so hard to see things from another viewpoint? Why do we come to blows over politics and religion?

Jonathan Haidt reveals that we often find it hard to get along because our minds are hardwired to be moralistic, judgemental and self-righteous. He explores how morality evolved to enable us to form communities, and how moral values are not just about justice and equality – for some people authority, sanctity or loyalty matter more. Morality binds and blinds, but, using his own research, Haidt proves it is possible to liberate ourselves from the disputes that divide good people.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | 1st edition (2 May 2013), Penguin |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Paperback | 528 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 9780141039169 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0141039169 |

| Dimensions | 19.8 x 12.9 x 2.93 cm |

by Carla

I read the review that gave this book low rating and I feel like they’re missing Haidt’s main point/ reason to write about this book. Haidt is concerned about social cohesion. And the thing is social cohesion comes from homogeneity or at least shared values or activities. Considering that the left is all about diversity, newness and difference, it makes sense that he would portray it in a somewhat negative light. The problem with insisting on difference and individuality, is that instead of making society adapt to you, it makes society notice your difference even more and hence, cause more bigotry and racism. Furthermore, I would like to point out something about diversity and multiculturalism. Multiculturalism is a pretty word that is tossed around when we’re talking about diversity, but it seems to me that very few people understand it.

Multiculturalism hardly means people living together as a community, it means having community within a larger community. Take the example of London, you have people from Eastern Europe on one side, the Polish only stays with the Polish, the Slovakian with the Slovakian and so on and so forth. Then, you have Black Jamaican who make up another unit. You have Black African (Anglophone and Francophone) – Nigerian, Ghanaian, Ugandan, Ivorian, Congolese…etc. Obviously nobody actually mix together. Nigerian stays with Nigerian, Ivorian with Ivorian and so on and so forth. Then you have Indians and Pakistani who stays with people who come from the same country as them. Even Italian in London usually stays with Italians. In fact not long ago, an Italian told me that there was a big association for Italian in London and that he was a member. There are many other group that I skipped because I couldn’t be bothered but you understand what I mean. And then you have the English – some accept this diversity (usually easier in good economic time), others merely tolerate it.

All group have a natural tendency toward self-segregation. But on top of that, these days we have an external pressure from the Left. The Left does everything it can to remind people how different they are from another, besides picking nonsense battle which erode social trust and our already tenuous social cohesion (i.e tearing statues, protests on university…etc).

The left in its haste to remake fail to understand that a) the world as it is though not perfect is way better than it use to be and b)that if they continue it will only lead us to a civil war. There is still poverty but anyone who’d read history would know that it’s nothing as it used to be (read for example Way to Wigan Road), racism though still a major issue is better now than it ever was. I should also point out something people always talk about how Trump brought a fascist state, about how much of a Nazi he is and so on and so forth. Do they not realise that if they were living in a true Nazi state they could not insult him, or his supporter the way they do on TV or even anonymously on social media? Trump is bad, but no he’s isn’t creating a new Nazi Germany or URSS. And really saying such things is terribly insensitive to the people who lived through those time.

By the way, I do not mean to say that injustice should not be tackled, but it has to be done in a pragmatic and useful way. Concretely, though I understand why he did this, what has Kaeparnick protesting the American flag accomplished besides increasing polarisation? Similarly, for the last couple of years I have heard using terms such as white privilege, white supremacists, old white men, patriarchy and other similar words in almost in every sense and often when they aren’t warranted. But what has it accomplished? It has created a backlash from conservative and annoyed liberals. You also have white liberals who have accepted those terms. But I believe for some, it is only a cool trend they have stumbled into, for other it is a form of religion which I’m not entirely sure they fully believe into, and the last group simply feel obliged.

To be clear, I do believe that in an unfair world, black people are more likely to suffer from unfairness than white people. There are various reasons for this bias and prejudice, the fact that black people are a numeral minority (10% of black in US, only 2% in UK and probably also about 2% in France) whereas white are the majority, lack of economic power of black people in the country they live, lack of economic country of African countries and cultural difference. So, in a sense I believe that white privilege exists, but I think that the way we go about talking about it is simply too divisive and does not promote understanding or even compassion.

I am very well aware of all the wrong white led country have done in history. Though if we’re being very fair about it, Arab countries (slavery) and Asian countries (mostly Japon have done the same [severe colonisation of neighbours]) have done similar misdeed. But really, we can’t expect someone to understand our point of view when we scream have him that the colour of his skin make him a bad person, even if he personally hasn’t done anything. Or when we say that all white people are basically evil. I understand where people are coming from when they say that. Exchanging with someone who has entrenched beliefs about you & your people, who simply cannot imagine that his experience is not the experience of everybody else or someone who is wilfully ignorant/ selectively chose morsel of history (many Conservative) can be very trying. Nonetheless, if our objective is to make a positive change then we need to change how we communicate.

Going back to the book, though Haidt says that Conservative have six moral foundation rather than the Liberal’s three, he does point out the flaws within the Conservative movement. Besides, Haidt never said that having the six moral foundation mean that you can’t be biases or that your reasoning is perfect. In fact, you could argue that he said the contrary. One more thing, someone pointed out that if Conservative score high in Loyalty how come they distrust the government. Well, this reading is wrong. Conservative do trust government to provide a good environment/ market, they trust the government’s words, including its lies. Essentially, they gov to rule the environment but not the individual. You should remember that they also score high in Liberty. Hence, it isn’t surprising that they do not want an external force to rule them.

I suppose some people aren’t happy just because he didn’t call them racist idiots. By the way, even after reading this book, I still have trouble reconciling my initial views with the picture Haidt presented. What I’m trying to say is that though Haidt’s book gave me a lot of insight, I still have much to digest.

I would recommend this book to anyone who want to understand politics and their neighbours with different political opinion.

There’s only one thing which the book is missing for me. It is a niggle and really, Haidt already did enough and couldn’t have looked at this. But I wonder how morality work/ develop across race. For example, a lot of black people are liberal/ democrats because this side have generally been against injustice and willing to do something for the lower section of society. But, could it be that some despite their skin colour are actually closer in their moral spectrum to the white conservative they despise (and who in turn may despise them)? More bluntly said, if instead of being black, they had been born white, could their political leaning be completely different because being white and conservative doesn’t come with the same baggage has being black and conservative? Really, if they white conservative could leave out his bias, could the black who have the same moral makeup as him get along better with him than with fellow black who do not have the same moral buds?

Really, I can’t help wondering how much who you are outside influence your political leaning despite who you are inside. If I had the opportunity I would have done a Phd on this. But ah…I’m way too busy. Has anyone ever thought about this?

In any case, as I said, highly recommended!

by Stephen McPhail

If, like me, you have ever thought that your moral and political take on the world is the only correct one, and perhaps you’ve now started to question these certainties, then perhaps this is the book for you. It’s pointless to recommend this book to the idealistically certain, because there’s no way they are going to read it.

by Sphex

The title of this astonishing book by Jonathan Haidt appears simple enough, and to be an unpalatable conclusion of any enquiry into the human condition. Who wants to think of themselves as righteous, let alone self-righteous? And who wants to read a book with the take-home message, however ancient, that “we are all self-righteous hypocrites”? Of course, when it comes to science, whether or not we like the conclusion has no bearing on its truth. But is it true? Insofar as I understand the arguments in the book (and Haidt provides copious references to the scientific literature), I’m persuaded by them (I’m also reassured that the author knows the difference between explanation and speculation). However, it should come as no surprise that any “portrait of human nature that is somewhat cynical” is not the whole story. Yes, we do “care a great deal more about appearance and reputation than about reality” and, yes, people are selfish, but it’s also true that people are “groupish”. I found this approach to understanding ultrasociality particularly fascinating, especially how it begins with cognitive psychology and then draws upon moral and political psychology.

The three parts of the book deal with three principles of moral psychology: intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second; there’s more to morality than harm and fairness; and morality binds and blinds. Alongside these principles come three striking metaphors: “the mind is divided, like a rider on an elephant, and the rider’s job is to serve the elephant”; “the righteous mind is like a tongue with six taste receptors”; “human beings are 90 percent chimp and 10 percent bee”.

The first metaphor aids our understanding of a crucial fact, that the mind is more than just consciousness, and that what is going on outside of conscious awareness matters. The elephant (broadly speaking, unconscious automatic processes) came first in evolutionary history, long before the rider (conscious controlled processes) appeared on the scene. The rider evolved to serve the elephant, and one of its main jobs is “to be the full time in-house press secretary for the elephant”. Hence we want to look good and will sometimes distort reality to preserve our reputations.

Haidt argues “that the Humean model (reason is a servant) fits the facts better than the Platonic model (reason could and should rule) or the Jeffersonian model (head and heart are co-emperors)”. However, Hume went too far in describing reason as the “slave” of the passions, since a slave is never supposed to question his master. “The rider-and-elephant metaphor works well here. The rider evolved to serve the elephant, but it’s a dignified partnership, more like a lawyer serving a client than a slave serving a master.” When it comes to designing an ethical society, the most important principle is to “make sure that everyone’s reputation is on the line all the time”, so that bad behaviour will always bring bad consequences. (Elephant and rider correspond to System 1 and System 2 in Daniel Kahneman’s

Thinking, Fast and Slow

.)

The second metaphor helps us get beyond “moral monism” – the attempt to ground all of morality on a single principle, such as avoiding harm. Haidt and his colleagues have developed an approach they call “Moral Foundations Theory”, which seeks to explain how our various moral principles might have come about. There’s no fixed number, but Haidt starts with five possible “taste receptors of the righteous mind”: care, fairness, loyalty, authority and sanctity. These correspond to five adaptive challenges: “caring for vulnerable children, forming partnerships with non-kin to reap the benefits of reciprocity, forming coalitions to compete with other coalitions, negotiating status hierarchies, and keeping oneself and one’s kin free from parasites and pathogens”.

Although Haidt stresses that morality is rich and complex, he’s not saying that “anything goes” or that all moral principles are equally good. His experience of living in India, where he studied a culture that was very different to that back home in America, was key to this broadening worldview. Just as we humans all have the same five taste receptors, but don’t all like the same foods, so the same righteous mind can produce a range of moral judgements. “Moral Foundations Theory also tries to explain how that first draft gets revised during childhood to produce the diversity of moralities that we find across cultures – and across the political spectrum.”

The third metaphor shouldn’t be taken too literally, and does not diminish the peculiar uniqueness of the human species. Indeed, Haidt was struck by a remark made by Michael Tomasello: “It is inconceivable that you would ever see two chimpanzees carrying a log together.” As Haidt puts it, if you see one hundred insects working together toward a common goal, it’s a sure bet they’re siblings. “But when you see one hundred people working on a construction site or marching off to war, you’d be astonished if they all turned out to be members of one large family. Human beings are the world champions of cooperation beyond kinship, and we do it in large part by creating systems of formal and informal accountability.” (Although Haidt doesn’t cite

The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life (Revised Edition)

, Paul Seabright’s book is another powerful argument celebrating human cooperation.)

So, we’re not always selfish hypocrites. “We also have the ability, under special circumstances, to shut down our petty selves and become like cells in a larger body, or like bees in a hive, working for the good of the group.” This is good news, in that this aspect of our nature facilitates altruism and heroism, not so good in that it also makes possible war and genocide.

I’ve barely touched on this book’s subtitle – “why good people are divided by politics and religion” – or on the rather uncomfortable conclusion (for anyone on the left of American politics, like Haidt himself) that Republicans appeal to a broader range of moral foundations than do Democrats. There’s so much to recommend that any synopsis will inevitably leave something interesting out. The author’s ability to handle sometimes difficult arguments with clarity, humour and style is, however, a constant throughout. Making things more complex than we think they are is often necessary, but rarely rewarding. In the case of righteous anger, which often demands a black-and-white judgement (“we are right, they are wrong”), moving beyond simplicity turns out to be a good thing. Understanding the righteous mind is worth the effort, and may even be the first step to a better place.