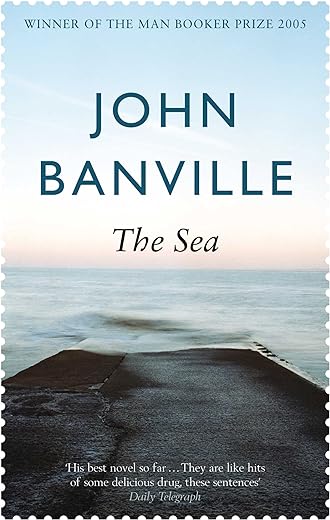

The Sea

£6.60£9.50 (-31%)

‘A masterly study of grief, memory and love recollected’ Professor John Sutherland, Chair of Judges, Man Booker Prize 2005

The Sea is John Banville’s Man Booker prize-winning exploration of memory, childhood and loss.

When art historian Max Morden returns to the seaside village where he once spent a childhood holiday, he is both escaping from a recent loss and confronting a distant trauma. The Grace family had appeared that long-ago summer as if from another world. Mr and Mrs Grace, with their worldly ease and candour, were unlike any adults he had met before. But it was his contemporaries, the Grace twins Myles and Chloe, who most fascinated Max. He grew to know them intricately, even intimately, and what ensued would haunt him for the rest of his years and shape everything that was to follow.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | Main Market edition (5 Mar. 2006), Picador |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Paperback | 272 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 0330483293 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0330483292 |

| Reading age | 18 years and up |

| Dimensions | 19.6 x 1.6 x 12.9 cm |

by Declan Henry

I consider myself a well-educated man but I defy anybody to read a John Banville novel and not have to make a few trips to the dictionary. He certainly has an expansive vocabulary at his disposal. He reminded me of Francis Mac Manus – an Irish writer long since dead. Mac Manus, too, used a pretty impressive vocabulary in his novels (I’ve read all thirteen of them) but his vocabulary appeared to blend in naturally to the text. Banville, however, uses archaic or technical words for effect, probably knowing that the reader may become stuck in the process. John Banville has often been described as a ‘writer’s writer’. From his interviews, it seems he has a healthy regard for his writing ability and has referred to some fellow writers as being ‘middlebrow’ in their literary offerings. What he would have thought of Mac Manus, I have no idea – nor do I know his views about fellow contemporary Irish writers.

The Sea, which won the Man Booker Prize in 2005, is about Max Morden, a retired art historian grieving for his wife who has died of cancer. Her death has rekindled bad memories from his youth when, during one summer, two of his friends (a girl who he had a crush on and her twin brother) were tragically drowned in the seaside resort town where he and his parents were holidaying. To ease his grief and to reconcile with the past, Max decides to go back to the seaside town (named Ballyless) and stay for a few weeks in a guesthouse that he much frequented during his childhood. The novel is full of witty observations, reflections and philosophical mutterings, along with many twists and turns – swaying back and forth between the current day and memories going back fifty years.

The whole story is wonderfully crafted, extremely well told and is paced beautifully throughout. Is it a great story? Not quite. It’s a good story though. Ultimately, I enjoyed it but it’s certainly not the most cheerful book I have ever read. This is essentially a novel about grief, so yes there are times when the reader will get a bit fed up. I know I did, and on two occasions over a ten-day period, I placed it aside for a day or two before resuming. Whether it was intentional or not, the novel stirred up in me a range of emotions, not uncommon with grief, so there were times when I felt sad, angry and tired. Having said that, I also laughed (sometimes out loud) at the Irish humour used in his character descriptions. I have just ordered the DVD of the 2013 film, based on the book, which stars Ciarán Hinds and Charlotte Rampling. It will be interesting to see how the film matches up to the book.

by FictionFan

“They departed, the gods, on the day of the strange tide. All morning under a milky sky the waters in the bay had swelled and swelled, rising to unheard-of heights, the small waves creeping over parched sand that for years had known no wetting save for the rain and lapping the very bases of the dunes. The rusted hulk of the freighter that had run aground at the far end of the bay longer ago than any of us could remember must have thought it was being granted a relaunch. I would not swim again, after that day.”

Max Morden has come to stay in a small seaside village he calls Ballyless, where his family used to spend their holiday each year when he was a boy. Now he is elderly, grieving the death of his wife, Anna, after a long illness, and seeking some kind of comfort in visiting the past. His thoughts and memories alternate between the time of her illness and of a summer much longer ago, when he first felt love and first encountered tragedy. That was the summer the Grace family rented the Cedars, when Max was around eleven and beginning the difficult journey through adolescence. At first he observes the family from afar, with a kind of lonely longing, but soon he will be allowed into their enchanted circle. His first obsession is with the mother, Connie, whose fleshy abundance sets his pubescent hormones ablaze, but it is the daughter, Chloe, for whom he eventually comes to feel an emotion that he slowly realises may be what adults call love.

The book is a wonderful meditation on grief and how it impacts us. Max’s grief for Anna is new, but it is the grief of the mature, perhaps elderly, when a death has come naturally and slowly, though cruelly. Banville speaks of this grief with profound empathy and sometimes with searing honesty, on how those of us observing may sometimes wish the dying would soon be over, partly for the sake of the dying but partly also for ourselves. He talks of ageing and the deterioration of mind and body, of withdrawal from the future and retreat into memories of the past. His writing is beautiful and full of emotional truth.

The other strand is a coming-of-age story as young Max begins to move out of childhood with all the turmoil of emotion, the narcissism and selfishness of first love, the sudden gateway to maturity but seen still through a childish lens. As he becomes friends with Chloe and her brother, there is much foreshadowing that leaves us in no doubt that this strand too will lead to grief, for an old tragedy that Max is reassessing from his now elderly viewpoint.

It reminded me in many ways of LP Hartley’s The Go-Between, and I suspect (hope, perhaps) that that’s deliberate. The golden, god-like stature to his mind of the family he becomes involved with, the long-ago summer, his coming-of-age and lack of full understanding of the adult world, the stirrings of first sexual awakening, and the perspective of a man now elderly looking back at this youth – all of these elements echo Hartley. My stock phrase in these situations is that if a writer is going to force his reader to think of another great writer, then he’d better make sure his own writing won’t suffer from the comparison. This is one of those very rare cases, perhaps unique, in fact, where I feel Banville’s writing is indeed as beautiful as Hartley’s. And there are plenty of differences to prevent it from feeling like a pale copy or worse, nor even an homage.

In place of Hartley’s heatwave, Banville uses the sea as his natural element and uses it wonderfully, to create mood and atmosphere and danger. He describes the tides and the shore so that we can almost taste the salt in the air and hear the seabirds shrieking overhead. Sometimes friendly, a playground for holidaymakers, but always the sea is given that sense of power and unpredictability that makes it something we must fear even as we love it.

But it is Max himself who is the heart of the story as we see him contrast what his young self thought adulthood would be with how his life actually played out. Nearing his own end, he is musing on the fundamental insignificance of any individual human to all but those nearest to him, and even to them solace will come in time. And yet he is comforted by that thought – if life is meaningless, then death is not to be feared.

“We carry the dead with us only until we die too, and then it is we who are borne along for a little while, and then our bearers in turn drop, and so on into the unimaginable generations.”

Beautifully written, emotionally perceptive and with enough touches of humour and self-deprecation to prevent the tone from becoming too overwhelmingly melancholy – for once, a truly worthy Booker winner!

by Ian Whyte

In Max Morden John Banville has created an elusive and reticent narrator. By the end of the book there is no certainty that the whole story has been told.