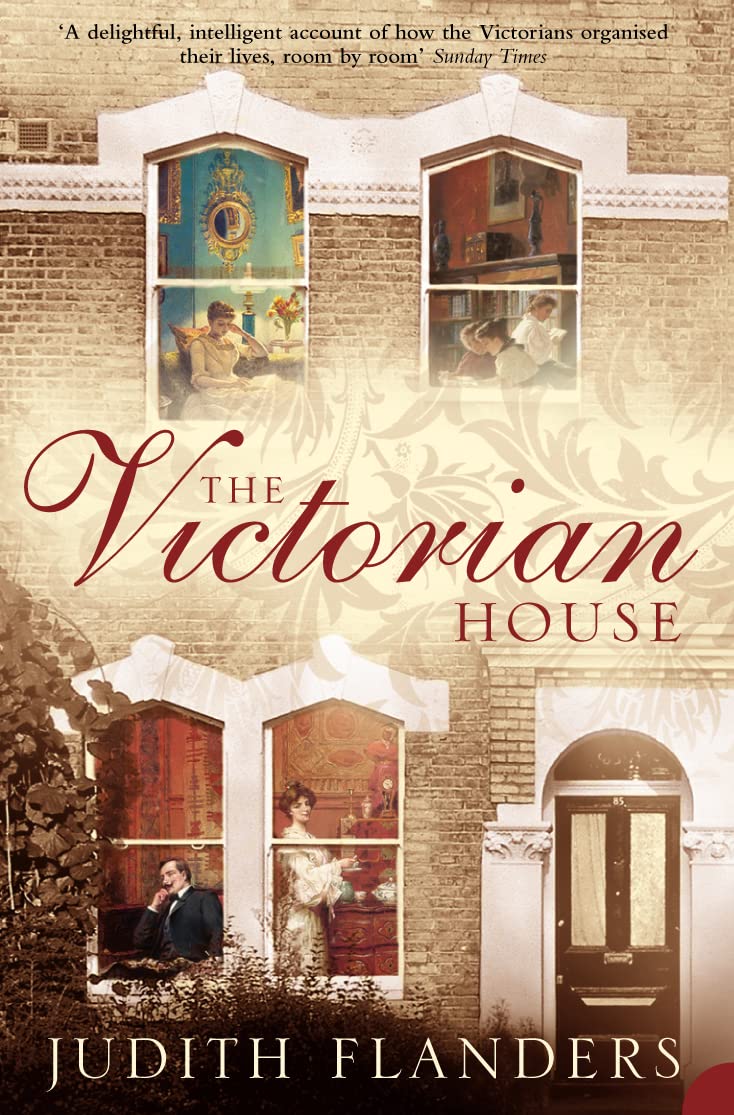

The Victorian House: Domestic Life from Childbirth to Deathbed

£13.70£14.20 (-4%)

The bestselling social history of Victorian domestic life, told through the letters, diaries, journals and novels of 19th-century men and women.

The Victorian age is both recent and unimaginably distant. In the most prosperous and technologically advanced nation in the world, people carried slops up and down stairs; buried meat in fresh earth to prevent mould forming; wrung sheets out in boiling water with their bare hands. This drudgery was routinely performed by the parents of people still living, but the knowledge of it has passed as if it had never been. Running water, stoves, flush lavatories – even lavatory paper – arrived slowly throughout the century, and most were luxuries available only to the prosperous.

Judith Flanders, author of the widely acclaimed ‘A Circle of Sisters’, has written an incisive and irresistible portrait of Victorian domestic life. The book itself is laid out like a house, following the story of daily life from room to room: from childbirth in the master bedroom, through the scullery, kitchen and dining room – cleaning, dining, entertaining – on upwards, ending in the sickroom and death.

Through a collage of diaries, letters, advice books, magazines and paintings, Flanders shows how social history is built up out of tiny domestic details. Through these we can understand the desires, motivations and thoughts of the age.

Many people today live in Victorian terraces, and so the houses themselves are familiar, but the lives are not. ‘The Victorian House’ will change all that.

Read more

Additional information

| Publisher | HarperPerennial, New Ed edition (2 Aug. 2004) |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Paperback | 536 pages |

| ISBN-10 | 0007131895 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0007131891 |

| Dimensions | 12.9 x 3.4 x 19.71 cm |

by L

I really, really enjoyed this book! It’s so engagingly written, but also well-researched with plenty of footnotes to guide my further reading.

by John Davison

I’m trying to read a book by a university academic on the evolution of the family, a subject which ought to be fascinating, but I find myself re-reading every phrase trying to penetrate the meaning behind the obfuscating verbiage (a bit like that sentence).

Judith Flanders, in contrast, shows how social history should be written: her style is absolutely clear, and she wisely lets the humorous and bizarre (and my goodness there is a lot of this) speak for itself.

I do sympathise, however, with the reviewer who jumped to the defence of the subject matter. I can’t quite buy into the idea that every Victorian was living a life of stifling convention and unrelieved discomfort, as I pointed out in a letter to the author:

“I am enjoying my way through The Victorian House, and am presently in the drawing room.

“Two comments:

“I grew up in a Methodist household in the 1950s, and we attended church and Sunday school on Sundays, and played Lexicon with Bible words only on Sunday evenings. The sermons were long and generally dull, but I loved the hymns, and there was no sense of Sunday being a depressing day – on the contrary, I remember it as an oasis of peace and reliability at the end of the week. Above all, it had its own distinct character, just as Saturday was the only day of the week with sport on the BBC, giving the football results an almost mystical significance.

“And whilst the portentousness of Victorian advice books seems amusing to us, I like to think that many Victorians enjoyed interior decoration and architecture for their own sake, and that for every social climber there was a simple soul lost in the beauty of the times.”

Update, March 2014: I am reading the book for the second time, and feel, more strongly than ever, this:

Judging the Victorians by the advice books and moral novels churned out in their era is a bit like judging 21st century society by the reality TV show “Big Brother”. At the peak of its popularity, Big Brother netted an average 5 million viewers per episode. In other words, more than 90% of the population never watched it. Yet to read the press at the time, you would think it defined how we live and think today.

And are we to believe that the UK in 2014 is a fiercely competitive society, because of the quasi-comic characters battling it out on “Come Dine With Me”?

The reality is that most people live their own lives, and don’t care that much what other people think, or what the “experts” say or do.

I am sure this applied to more Victorians than Judith Flanders believes and would have us believe.

As for the accounts of the abuse, exploitation and degradation of servants: it existed and it was terrible, but we know that it was not the whole story, and that many employers were kind, good-humoured and democratic.

So, while thoroughly recommending this book, I would also recommend reading Michael Paterson’s “Brief History of Life in Victorian Britain,” to get a view of the era that is more generous and more sympathetic.

by T. K. Elliott

This book was excellent.

This is not a book for people who are already knowledgeable on the topic of domestic daily life during the Victorian age in England. Flanders does, however, manage to combine an informative overview with a considerable degree of entertainment value – especially if you read the footnotes, where most of the humour is.

This is a particularly useful book for anyone hoping to write about the period, since Flanders does not get bogged down in detail, but she does manage to get the ‘feel’ of the period very well indeed. One thing that particularly struck me is the sheer filthiness of the cities (particularly London, as the largest city) – Flanders does not just say “it was filthy” but demonstrates by discussing little adjustments people had to make, like not putting out a white tablecloth until a short time before the meal, or it would go grey. This level of atmospheric pollution is something that we just don’t have to deal with in the UK any more, so it’s hard to imagine without the examples Flanders gives.

Another interesting area is the illustration of how limited many middle-class women’s lives were – again, something that we find it difficult to appreciate from our twenty-first century standpoint. We might intellectually know that the Victorian period was probably the one in English history where women’s rights and status in society reached their lowest ebb, but Flanders provides illustrative facts, including that since women were supposed to spend their lives catering to their families (particularly the men), pretty much the only way for a woman to get some time to herself was to be ill – which provided a cast-iron excuse for retiring to one’s bedroom and closing the door. It provides an interesting alternative viewpoint on the fragile Victorian lady – women’s health was generally poorer than men’s because of their poorer diet and lack of fresh air and exercise, but being a professional invalid definitely had its attractions for any woman who wanted to escape the endless round of service to others.

This is a book I shall probably refer to again and again.

by Anne

The author has written an excellent social history about the domestic life of ordinary Victorians and based it around the rooms in the house. This is a very clever way in which to write this book and makes it very, very accessible for the reader of popular history. She links each room with one stage in life (the nursery for birth, the drawing room for the woman as household manager, the dining room for the hostess and the sickroom for death for example). This is a clever conceit and doesn’t always quite gel as well as the author may have liked but it enhanced the book considerably by breaking down the aspects of life lived in a domestic sphere into manageable chunks.

This book deals with the domestic side of Victorian life and thus it deals a lot with the role of the woman as the household manager and hostess whilst the man of the family earned the money and dealt with life outside the home. The author deals with the mass of middle class families more than the aristocracy or the very poor and breaks down some of the myths about Victorian living, especially with reference to the role of servants. She describes how life was lived together with the furnishings and equipment which would have been necessary. My mother-in-law also read this book which she very much enjoyed and recognised many of the techniques and equipment as still in use in her childhood in the 1930s in a small mining town.

There are lots of fascinating nuggets here, revealed in an easy to read style broken up with plenty of illustrations (I had the paperback version of the book which has some colour plates in three sections and line drawings included in the text). Very enjoyable and informative